Safety First

Like a severe and utterly serious version of Stanley Kubrick’s 1964 satirical dark comedy Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb, you would think that Fail Safe would have been the original release in theatres that was then later spoofed, yet that is not the case. Released approximately six months later in the same year, as you might imagine, it led to very poor returns at the box office – dare I say it (as the film deals with this subject matter)... it was a bomb! Despite that, over time, it has become a bonafide classic. Based upon Eugene Burdick’s 1962 novel of the same name and directed by Sidney Lumet (Dog Day Afternoon), he introduces us to our main players by way of little vignettes.

-

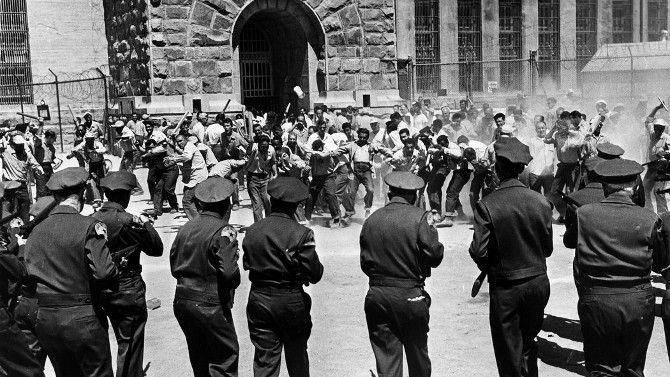

What a Riot

Riot in Cell Block 11January 14, 2018With a stellar cast, those behind 1954's Riot in Cell Block 11 did not take the approach of procuring the biggest names available, instead, they brought together a group of character actors that lived their parts – and all surrounded by real prisoners and guards, who played extras during production. Directed by Don Siegel (Invasion of the Body Snatchers; Dirty Harry), and produced by Walter Wanger (inspired to make the film after serving a four month prison sentence and being wholly unnerved – he was jailed for shooting his wife’s [Joan Bennett] agent, Jennings Lang, whom she was having an affair with – one bullet penetrated his hip, the other, his groin – clearly we know what he was aiming at), the team cast Neville Brand as a convicted murderer who heads up the riot (the former World War 2 combat soldier was the fourth most decorated American from the period), while his ‘Crazy’ second in command was developed by Leo Gordon (another convict who was shot in the gut during an armed robbery).

-

Morally Bankrupt

The CheatJanuary 12, 20181930's Hollywood films are rather intriguing. Though hit hard by the Great Depression (much like everywhere else), the escapism of movies still brought 60-75 million people into theatres each and every week (and, these numbers are for the worst times of the decade). The 30s also harkened in the era of the talkie – quickly putting an end to the silent film industry. The decade can also be split into two distinct periods: the five years before the Motion Picture Production Code (sometimes called the Hays Code) officially came into being (often referred to as the Pre-Code), and the five years after it was put into place – meaning that there was now a strict set of rules and regulations that were being strongly enforced. Both a curse and a blessing (many of the most talented directors found creative and visually clever ways to circumvent the Code – DeMille and Hitchcock are two that immediately come to mind), it did limit creative freedom in a major way, as sex, violence and language were severely censored – movies could no longer depict lacking morals (that is, unless the behaviour would be punished in the end).

-

Running Down a Dream

The FreshmanJanuary 7, 2018Setting out to film (firstly) the climactic football scene at the Rose Bowl (stadium) in Pasadena, California for his 1925 feature The Freshman, Harold Lloyd soon felt like he was lost – unable to sense the character and his feelings, not able to hit the right tone for his collegiate protagonist. Scrapping the work, he decided to return to Hollywood and shoot sequentially – a rarity for any motion picture. It was typical for Lloyd and his team to come up with the major set pieces first (a perfect example being the football sequence) – shooting it at the very beginning, but in this case, Lloyd felt like this format was better suited, as it would add depth and continuity as the actors grew into this very character driven story. Becoming a major spectacle (and Harold Lloyd’s highest grossing film), it spawned an immense number of college sports movie knock-offs that would dominate the theatre scene for the next several years (a prime example, Lloyd’s character is utterly inspired by a fictional college student found in a fake movie made up for this one titled “The College Hero” – two years later, The College Hero was released by Columbia Pictures). Following Lloyd’s Harold ‘Speedy’ Lamb (notice his nickname is the title of his 1928 New York set picture), the teen is heading off to Tate University – a school that is football crazy. While en route, he meets a shy, sweet hearted ingenue named Peggy (Jobyna Ralston) – timid love at first sight.

-

Poison Pen Letter

A Letter to Three WivesDecember 13, 2017As three volunteering women rush aboard a river-boat that takes children from underprivileged families on an annual daytrip, they receive an unexpected letter from one of their friends explaining that she has left their quaint little city behind with one of their beloved husbands in tow, putting each into a state of crisis. This is the suspenseful hook for the 1949 romantic drama A Letter to Three Wives, written and directed by Joseph L. Mankiewicz. The letter writer is voice over narrator Addie Ross (Oscar winner Celeste Holm) – the sultry, well connected dame is never shown, and the husband she has run off with is also left in the dark until almost the very end. Doing their duty as good citizens, Deborah Bishop (Jeanne Crain), Lora Mae Hollingsway (Linda Darnell), and Rita Phipps (Ann Sothern), three longtime friends, take the kids on the cruise and stop off to have a picnic, each flashing back (at a moment when they are not busy) to a time in which their significant other may have shown their true colours in regards to Addie.

-

Boy Meets Girl

NeighborsDecember 6, 2017Long before Zac Efron and his fraternity bros started terrorizing new parents Seth Rogen and Rose Byrne in the 2014 comedy Neighbors, there was another movie with the same name, a superlative 1920 short from the great Buster Keaton (one of his first four shorts on his own). A tale of star crossed lovers, The Boy (Buster Keaton) and The Girl (Virginia Fox – originally one of Mack Sennett’s Bathing Beauties, she would marry major Hollywood mogul Darryl F. Zanuck, retiring from the business just a few years later) are madly in love, though the fence that separates their tenement apartments might as well be topped with barbed wire and armed with snipers, as their families despise each other – a feud rivalling the Montague’s and Capulet’s. Both fathers are especially involved in keeping the pair apart, though The Girl’s giant sized Father (Joe Roberts) is a much bigger threat than The Boy’s equally diminutive dad (played by Buster’s own father, Joe). Early each morning, they slip notes through a hole in the fence to communicate.

-

Grave Steps are Taken

The Strange Love of Martha IversNovember 26, 2017Uniting a superlative film noir cast, 1946's The Strange Love of Martha Ivers, directed by Lewis Milestone (a two time Academy Award winner, one of which he earned for All Quiet on the Western Front), begins with a triumvirate of childhood friends witnessing a crime which forges a unique bond between them, it informing their respective directions into adulthood. Building off of her performance in Double Indemnity two years earlier, Barbara Stanwyck, playing the title character, once again proves why she is one of the all-time great femme fatales. . . a calm, controlled, ruthless Machiavellian puppet master, she not only pulls the strings of her weak and feeble alcoholic husband Walter O’Neil (Kirk Douglas in his first film role – and against type from what we would later know) – who truly loves her, but she also has a manipulative control over the entire city in which she lives – owner of the plant that gives its people their jobs, the police that protect it (thanks to her husband, who is the district attorney), and everything else in between.