An Attaché Case

In 2025, dare I say that it’s nice to be highlighting a film made for mature audiences. Avoiding the pratfalls of sequels, remakes, comic book movies, and overly costly bombast, Black Bag, written by David Koepp (Mission: Impossible) and directed by Steven Soderbergh (Traffic), is most easily described as an old school spycraft feature. Opening with an extended tracking shot of spy George Woodhouse (Michael Fassbender) making his way through a happening nightclub in London, his contact soon informs him that there is a rat leaking some sort of tech software named Severus from within the agency. If there is one thing Woodhouse despises, it’s a liar, so he invites all of the suspects to a dinner party to try to get to the bottom of it.

-

Take the Long Way Home

LionFebruary 8, 2017A little ragamuffin – strong willed, feisty and wily, finds himself waking up on a bench at a train station with his older brother nowhere in sight. With his mother at home, he shouts for his missing brother, but nothing comes of it. He searches an abandoned train, only to fall asleep sometime in the night. When he wakes, the still empty train is moving. When it finally stops, he finds himself in Calcutta, nearly two thousand miles away from his hometown, not knowing the Bengali language or having anywhere to turn. It is this bizarre and unfortunate circumstance that is the genesis and heart of the story Lion, first time filmmaker Garth Davis’ moving drama. The young boy is Saroo (Sunny Pawar), his fatherly older brother is Guddu (Abhishek Bharate), and his caring impoverished mother is Kamla (Priyanka Bose). Though theirs is a tough life in a rural Indian town, filled with hardship and many struggles, love permeates their family.

-

Blood Simple. . . Anything But

Blood Simple.February 3, 2017With two feet firmly planted in the historic noir genre of the 1940s and 50s, Joel and Ethan Coen went about making their first feature film, Blood Simple.. Though it was not, by any means, that ‘simple’. Creating a trailer long before production (it has Bruce Campbell in it – who never appears in the final motion picture), strangely enough, it does not feel entirely compatible with their final product, but somewhat like a distant relation to the iconic cult horror classic Evil Dead. On the advice of Sam Raimi (director of the above mentioned movie – who helped advise the brothers), the Coen’s went door to door with a projector and their trailer, seeking out investors. Think of it as the original GoFundMe. In just over a year, they raised the needed capital and got to work on their film – which, in case you thought that I made a mistake up above, contains a period after ‘Simple.’. A striking neo-noir, the title comes from an old Dashiell Hammett novel, "Red Harvest", a term that highlights the muddled, jittery and anxious mindset of people who have had a protracted immersion in violent affairs.

-

Star Pick with Sally Kellerman

Rebel With a CauseViva Zapata!January 31, 2017

Rebel With a CauseViva Zapata!January 31, 2017There is a scene about a quarter of the way into Elia Kazan’s Viva Zapata! where our protagonist, Emiliano Zapata (Marlon Brando), has been arrested for attempting to save the life of a peasant who has been unlawfully arrested. Failing, a number of the impoverished, who witnessed the attempt, plead for Zapata to hide in one of their homes. Moving on, he is soon arrested, and the villagers clap with whatever they have in their reach; working tools, rocks or any other implements, as a way to show their support for the hero as he is ushered away. As the officers transport the man through the wilderness, people pour out of the mountainous forest – soon, droves are leading, following and walking beside the police procession. Eventually overwhelmed by the masses, they free the man, aware that they will never be able to manage the united crowd. It is this scene that perhaps best exemplifies the film. A heartfelt sequence, it shows that solidarity in the face of oppression, that boldly standing up for what is right, is a righteous, albeit difficult stance.

-

Star Pick with Michael Dickson

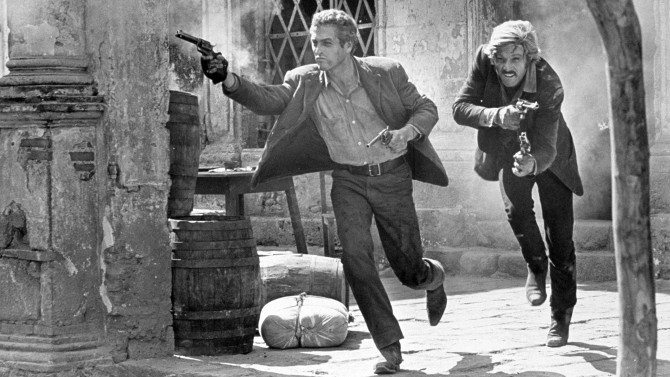

Butch and Sundance Ride OnButch Cassidy and the Sundance KidJanuary 24, 2017

Butch and Sundance Ride OnButch Cassidy and the Sundance KidJanuary 24, 2017One of the most prolific westerns (and sometimes argued to be the last great western) to come out of Hollywood, George Roy Hill adapts William Goldman’s script that brings to life the real, mythical-type figures of Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. The background of the script is quite something, with Goldman sending it out to all of the studios – only one was interested (and that was if he made a major change to it). Instead, a few minor adjustments were made, after which Goldman discovered that every studio in town now desperately wanted it. In the end, it was 20th Century Fox President Richard D. Zanuck (son of co-founder Darryl F. Zanuck) who purchased the screenplay for a whopping 400,000 dollars (the biggest sum ever spent on a script up to that point) – and 200,000 higher than he was allowed to spend. Putting his job on the line, it was a wise choice, as it became the highest grossing motion picture of 1969. Goldman ended up winning the Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay. Originally titled ‘The Sundance Kid and Butch Cassidy’, Zanuck didn’t find that the title sounded right when it was reversed to its final iteration – funnily enough, it now feels utterly awkward in its original form.

-

Don’t Let This Fence Keep You Out

FencesJanuary 21, 2017Based upon a stage play, Denzel Washington utilizes August Wilson’s adaptation of his own drama Fences to tell an engrossing story of an African American family growing up in the 1950s. Both literal and figurative, Troy Maxson (Washington) is building a fence in his backyard, though it is also a symbolic barrier placed up to guard against his own projections of the impending Grim Reaper (fighting off a serious case of pneumonia, aka. Death, at a young age, he is constantly vigilant for his return – though not afraid in the least). He enjoys the chess match that they play over time. It is also a powerful allegory for the walls he builds between himself and different members of his family. On the opposite spectrum, it is also a way for his wife Rose (Viola Davis) to put up something that will protect her family, keeping them safe on the inside, while keeping unwanted dangers at bay.

-

The ‘Eyes’ Have It

The Secret in Their EyesJanuary 17, 2017The saying ‘the eyes are the windows to the soul’ is perhaps no better explored than in the Argentinian Academy Award winning (for Best Foreign Language Film) 2009 motion picture The Secret in Their Eyes. Though the face is often inscrutable, as many put on masks to hide their true feelings from those around them, the eyes truly show the love, hate, lust, passion, pain regret and confusion that lies just below the mysterious facade. Co-written, directed, edited and produced by Juan José Campanella, the story follows retired criminal investigator Benjamín Esposito (Ricardo Darín) as he contemplates the innumerable hours he spent on the Liliana Coloto (Carla Quevedo) murder case (it is his white whale) by way of writing a novel. Struggling with a proper beginning, he visits Judge Irene Menéndez Hastings (Soledad Villamil), who he worked with all those years ago (the murder took place in 1974).