As viewers, we act as voyeurs, observing the intricacies of the character’s lives – their actions, interactions, relationships, affairs and countless other physical or mental manoeuvres. Films can act as therapy and relief, or can cause self-reflection, disgust or numerous other emotions depending on how we react to what we are scrutinizing on the screen. It may resemble something we have done in our own lives or could illustrate a seedy side of life that we have never even contemplated. A number of directors have cleverly infused their stories around the concept of voyeurism, adding a deeper level to our viewership, to great effect. The first filmmaker to come to mind is Alfred Hitchcock, who masterfully concocted Rear Window and Psycho around these themes, though there are countless other examples: Michael Powell’s Peeping Tom, Peter Weir’s The Truman Show and Stanley Kubrick’s Eyes Wide Shut are merely three more that fall within this category. A European motion picture that once again delves into this intriguing topic is Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck’s 2006 movie The Lives of Others.

Set in East Berlin during the year 1984 (a fitting date to be sure), we observe the works of a cold-hearted Stasi (or secret police) officer named Gerd Wiesler (Ulrich Mühe), a trained interrogator and spy who has been told to watch famed playwright Georg Dreyman (Sebastian Koch). The writer is considered to be a great socialist who scribes plays that depict the story of how individuals change over time, yet all within a positive East German outlook. With friends in high places, the man has never been spied on by the state, yet Oberstleutnant Anton Grubitz (Ulrich Tukur) – who knows how to play the game to advance in life, agrees with the powerful Minister Bruno Hempf (Thomas Thieme) that no one is above suspicion and the artist should be monitored.

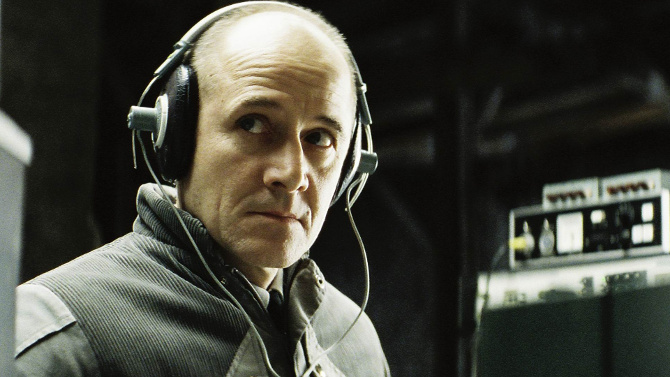

This is where Dreyman’s old school chum Wiesler comes in – sneaking into the author’s abode to bug it. He sets up his eavesdropping station in the attic of the apartment building where he listens to the man and his girlfriend, iconic actress Christa-Maria Sieland (Martina Gedeck), day and night.

The East German officials that we watch cannot be called likeable characters, for we soon learn that the only reason that the gluttonous Hempf wanted Dreyman investigated was because he is obsessed with his girlfriend – and is using his powerful position to blackmail her into sleeping with him.

The themes of The Lives of Others work on many levels. At one point the music loving Dreyman explains that Vladimir Lenin once said that “If I had kept listening to it [Beethoven’s Appassionata], I won’t finish the revolution”. In many ways Wiesler is the Lenin stand in – a stone cold individual (whose face is always stoic) who pushes his emotion aside for the duties that he must perform for the good of the country. He is loyal to the state, never having delved into the underground western music or literature that others have broken rank to do. Yet, as a voyeur, he is slowly pulled into the lives of these two normal individuals – discovering in the process they are just trying to survive and make their lives better. He also slowly understands the corrupt and un-state-like manner of his school chum and the unscrupulous Minister. It is powerful for us to observe how the voyeuristic man slowly changes over time – much like in one of Dreyman’s plays. Wiesler begins to ‘borrow’ the author’s books and is moved by Dreyman’s heartfelt piano playing after the man learns of the shocking death of one of his friends.

It is this death that drives the straight-laced Dreyman to secretly write a story on the staggering number of suicides that occur on the East side of the Berlin Wall – using his more rebellious friends to help him get it across to the West so that it can be printed. He must hide his actions by using an illegal typewriter that uses red ink – one of the only times the colour is seen on the brown, green and grey infused East German palette.

The Lives of Others is best left discovered for oneself, after all, a voyeur should witness things firsthand. What I can say is that Donnersmarck’s vision feels authentic – it is as though we have been transported to East Berlin in 1984. The history feels right, from the story and characters, to the realistic costumes and settings. Gabriel Yared’s score must also be highlighted. His main theme encapsulates the mystery, intrigue and voyeuristic nature of the tale, while his love motif is equally as moving in an utterly different way.

It was powerful to learn that the actor who played the state sanctioned spy, Ulrich Mühe, experienced the invisible eyes firsthand before the reunification of Germany. After the fall of the Berlin Wall, he found evidence in his Stasi file that he was being observed and reported on by four of his acting friends as well as by his wife. An eerie similarity indeed.

In the end, The Lives of Others deserves a space on a list along with all of the other voyeur-related pictures mentioned above. There is a reason it won the Academy Award for Best Foreign Film in 2006. Donnersmarck provides us with a supremely nuanced movie that adds a rich flavour to the genre, as we know that stories such as this are all too true – both in the historic past and in the present day. It is multi-layered and faceted, and we gain a richer appreciation of all that is at work with multiple views. Plus, it has a fitting ending that wraps the story up in a more than solid way; as a different conclusion may have ruined the experience. So, don’t sit on the wall – dedicate yourself to seeing this excellent motion picture.