A person with a past erased, no true present, and a future that is very much in jeopardy, the German film Phoenix (2014), written/directed by Christian Petzold and starring Nina Hoss (perhaps one of the best working director/actor teams outside of the United States – this is their sixth of seven movies together thus far), is an intimate historical character study revolving around one of the greatest atrocities in human history.

Set just after the conclusion of the Second World War, Nelly Lenz (Hoss) has recently returned from a concentration camp. A singer who was shot through the face in the dying days of the war, she somehow survived, passed over by the workers who thought she had died from the bullet wound.

Aided by her longtime friend Lene Winter (Nina Kunzendorf) – a woman who was also in the camp, she has taken over the role of organizing everything in her life. . . including finding her a reconstructive surgeon.

With a vicious facial wound that needs to be repaired, she walks around like the Invisible Man, her face bandaged, her visage erased evermore. These sequences are stunningly shot, flashbacks always leaving her in dark shadows, photos discovered from her past never clear enough for us to truly make her out. . . visual symbolism that her past, no matter what she does, is never to be truly recovered. Though she simply desires her original face, the doctors are not confident.

When she finally does remove the bandages, it is perhaps no surprise that she only looks a bit like her former self. Suffering from a serious form of trauma, Nelly looks around for help, but sees none. Her entire family has been wiped out of existence, most of her friends as well, and Lene cannot offer her the aid she truly needs. Latching onto the idea that she must try to find her husband Johnny (Ronald Zehrfeld) – for some reason she believes he can help her recapture her former self, Lene warns her that she should not go looking for him.

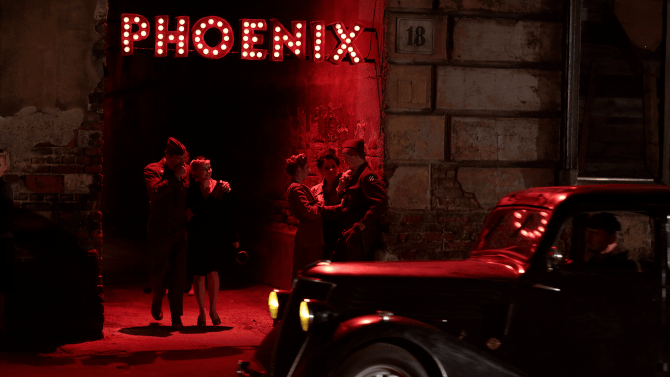

Ignoring that advice, she eventually finds him cleaning tables in a sketchy nightclub called Phoenix. . . though, because of her new face and introverted, fragile and dehumanized personality, he does not recognize her. Returning each night like a lost puppy dog, it does not take long for Johnny to notice her, not as his wife, but as a lookalike for her. Hatching a scheme, he asks the woman to act as his wife so that he can get her inheritance (something he cannot get without her). She agrees. . . as she is so desperate to be recognized as herself, and he slowly starts to tutor her into being that woman. A most bizarre game that could be deemed cat and mouse, will Johnny recognize his wife’s lookalike as the real thing? Might Nelly finally find what she is looking for in Johnny? And, intriguingly, who betrayed Nelly. . . as she was quite well hidden before being discovered by the Nazis.

A deep, powerful motion picture, Phoenix’s simple story never betrays itself, always beholden to the actors and their performances. Likewise, the cinematography by Hans Fromm only adds to the mystery. Fusing noir elements (the blacks sharp, crisp and surreptitious) with the nightclub’s neon red almost a Technicolor-like Vertigo hue (immediately reminiscent of Hitchcock’s tale of a haunted former police officer who is supposedly tracking a woman with multiple personalities), all of the elements (including Stefan Will’s score) come together to create a complete picture oozing atmosphere and emotion.

With a two-pronged title referencing both the film’s nightclub and the mythical bird that is reborn from its own ashes, Phoenix’s final scene is an example of a moment that could either make or break the entire work. In this case, it succeeds and elevates the entire piece – an emotive moment of pain and beauty which combines visual simplicity and emotional complexity, a loss with a discovery, a death with a rebirth, both an ending and a beginning, crippling guilt and a freeing from the chains that bind, as well as a song and voice that means so much more than any word that could ever be spoken – in other words, an impactful duality that in just a few minutes, captures everything that needs to be said and then leaves us alone to contemplate it.

This film is in German with English subtitles