Al Roberts: “That’s life. Whichever way you turn, Fate sticks out a foot to trip you.”

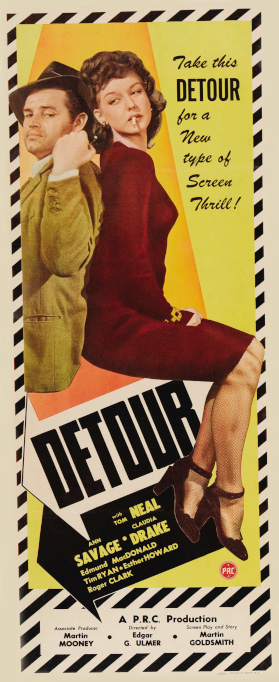

You know you’ve got a budgetary problem when you find yourself on Poverty Row. For those of you who do not know, this was the slang term used for a group of low budget Hollywood B movie studios that existed in the City of Angels from the 20s to 50s. Transcending these financial constraints to make a quality film noir, director Edgar G. Ulmer used all the proverbial tricks in the book to develop Detour (1945).

Told in a most unique way, a quasi-soliloquy narration transitions to nightmarish flashbacks as Al Roberts (Tom Neal) recounts his fatefully nihilistic tale (you might never see a more downtrodden visage). A cynical man, even before his girlfriend (closing in on fiancée), Sue Harvey (Claudia Drake), decides to leave him to make her own breaks in Hollywood, he is the prototypical down on his luck protagonist. It’s not like he doesn’t have a skill – a piano virtuoso, he can only find a job tinkling the ivories at a crummy nightclub in fog strewn NYC (fog was a useful tool for low budget productions that didn’t have the money for sets).

Deciding to follow his girl to Los Angeles, he doesn’t have the cash for any true mode of transportation, instead attempting to bum a ride cross-country. Though much of the movie was either filmed in one apartment room or in a car located in front of a rear projector screen, the few moments they did shoot in the desert are something wholly different from your prototypical film noir – the sun baking his brow, sweat beading down, suit and fedora no longer a disguise for the shadows, but rather a burden that he burns in.

And, just when it seems like luck is finally on his side. . . after all, L.A. bound Charles Haskell Jr. (Edmund MacDonald) has picked him up, the man drops dead as he is taking over the driving duties. A drifter in an impossible scenario, if Roberts waits for help, the police will likely finger him anyway, so he nabs the guy’s wallet, suit, money, and car. . . deciding to continue on his way.

Seeming like paranoia couldn’t reach a higher pitch, Roberts picks up a young female on the road, Vera (Ann Savage – a fitting surname that fits her character), only to soon find out she knew shady Haskell. Not what you’d expect from a femme fatale – sultry seduction followed by a knife in the back, Vera’s the type of woman who likes for the knife to be ever visible. Not unattractive, you would think her disheveled look (dirty clothing and grease running through her hair) might bring her some sympathy, yet she is pure terror. Darker in the day than the dead of night; unadulterated anger, ruthless aggression, and sadistic pleasure permeate each and every pore. Her essence might only be matched by Roberts’ own uncontrollable and irrational guilt, this all-controlling feeling forcing him to buy into her blackmail. An intriguing note worth mentioning, there are a few minuscule moments where, as they are bickering (Vera forcing them to pretend to be a married couple), there is a glimmer of sexual tension – subtle hints that so much confined anger can sometimes turn into something different. . . yet, as soon as this arises, Vera will shoot something along the lines of, “Shut up, yer makin’ noises like a husband”.

Now calling the shots, Roberts has lost any chance of self-correcting his already-working-against-him fate. . . after all, she knows he has assumed Haskell’s identity (and has never believed that he didn’t kill him). And, let’s face it, you just can’t win when someone’s all too comfortable saying, “If I’m hanged, all they’d be doing is rushing it”. Might Roberts ever get a chance to regain some leverage back from the dangerous femme? Will he ever make it back into the arms of his beloved Sue? Or is he just another unlucky loser, destined to fall prey to the unfairness of life?

Throwing everything at the screen but the kitchen sink, Ulmer pulls from many a source – German Expressionism (look for the oversized coffee cup at the beginning of the movie as a warning that this is an almost haunting tale), the growing noir trends (the lighting, especially during the soliloquy sequences is absolutely stunning; while the dialogue is at its stylistic best), classical music (Chopin and Brahms giving an almost operatic tragedy to the piece), and his own émigré history (a man with no true home – yet with so much skill but no fruitful job to show it off), to weave a tale as desolate as the desert much of this story is set in. The narratives other main feature is its idiosyncracies that vary it from other noirs – the above mentioned femme fatale (arguably the most nasty in the history of the sub-genre), the burning desert sun rather than unyielding city shadows, and the lowly budget (continuity errors – like the film being reversed for a shot to save money. . . it looking like Roberts has somehow made his way over to England) giving this motion picture a most distinctive quality.

An existential tale for the ages, Detour’s hard edges have in many ways kept it timeless – its dark pessimism still making it ultra relatable for modern viewing. Surreal yet believable, it meets a glorious milieu that clashes together to provide an unquantifiable veracity – talk about an oxymoron. That there has long been a rumour (bandied about by Ulmer himself) that he shot the movie in just six days only adds to this Poverty Row legend. And perhaps this is what makes it so special – that beyond the limited budget, Ulmer was still able to create one of the most atmospheric features of all-time. A final note – if you want to read the perfect noir script, take the time to look up this film’s star, Tom Neal’s bio – it’s no less bleak. So, crack this egg and discover just how hard boiled they come with this noir gem, there’s no doubt its atmosphere will strangle you.