Baron Wolf von Frankenstein: I should turn you over to Inspector Krogh!

Ygor: No! Krogh no want dead man, Ygor is dead!

Baron Wolf von Frankenstein: What are you talking about?

Ygor: They hanged me once, Frankenstein. . . they broke my neck.

Baron Wolf von Frankenstein: Hanged you. . . well, why did they hang you?

Ygor: Because I stole bodies. . . they said. . .

Celebrating its 80th anniversary this 2019, the Son of Frankenstein (1939), directed by Rowland V. Lee, is the third film in the franchise – following Frankenstein (1931) and Bride of Frankenstein (1935), the last to feature Boris Karloff in the role of the monster, and the first to insert Bela Lugosi as Ygor. . . pairing two of the most iconic horror actors together was a smart move for Universal – the movie was a mammoth hit.

All centred on the dramatic, pencil mustached Baron Wolf von Frankenstein (Basil Rathbone – arguably the greatest portrayer of Sherlock Holmes), he is the son of the original mad doctor. . . and is returning home with his slightly twitchy wife Elsa (Josephine Hutchinson) and young son Peter (Donnie Dunagan) – a cute, fear nothing lad whose accent is an eccentric delight, to claim his inheritance – much to the chagrin of the still terrified townsfolk.

Making their home in the medieval castle Frankenstein (that sits upon a boiling cave full of sulphur), its gothic renovation fills the gargantuan looming windowed and doored abode with eccentric, off-kilter angles, and palpable chiaroscuro lighting. And, lest we forget the trap doors. . . for what is a spooky castle without a few mysterious hidden panels and creaky staircases.

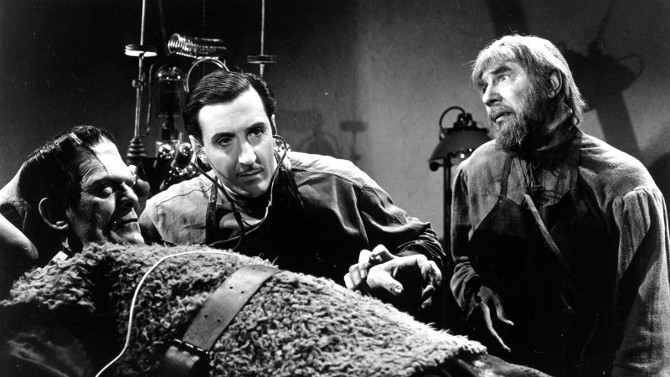

Despite being hanged to death, Ygor (Lugosi) still lingers around, a lurking shadow that continues to haunt the memories of the foggy, often storming surrounds. Eventually making contact with Baron Wolf, Ygor reveals that the believed to be dead monster (Karloff) is, in actuality, alive – though rests in a translucent sort of coma.

Intrigued and disturbed, Baron Wolf cannot help but attempt to resurrect both the monster and his father’s shambled legacy – one that should, in his mind, read ‘creator of life’ instead of ‘creator of death’.

As the townsfolk percolate in the valley below the castle. . . mustering up the courage to once again form a gang of pitchfork wielding vanquishers of evil, the only man brave enough to enter the stone edifice is Inspector Krogh (Lionel Atwell), a man who had his right arm ripped off by the monster when he was a mere child. It is this stiff, robotic armed officer that Kenneth Mars so beautifully satirizes in Mel Brooks’ Young Frankenstein (right down to the dart scene). Both wily enough to realize that something is up and sympathetic enough to give the young family the benefit of the doubt (despite their name), Krogh often drops in, sometimes for business, other times as a dinner guest.

Of course, this would not be much of a movie if the monster did not rise again, and the slowly cracking Baron Wolf soon realizes that his original thoughts were perhaps a tad naive. . . not realizing that the maniacal Ygor was actually the one who controlled the simple yet warped mind of the hulking creature. Soon, villagers begin to die, as do servants working within the castle. . . and, three films in, we must start to wonder if there is really anything that can stop the lumbering Frankenstein monster. Likewise, can anything be done to Ygor – especially about his poor hygiene and somehow even worse dental care?

And, though we call the creature a monster, this film, like the others in the franchise, continues to show moments of the giant’s humanity. We see his traumatised face looking in the mirror – pained by his disfigured visage (especially compared to Baron Wolf), later, we see him think better of killing a child (perhaps learning from the flower picking incident). . . while a third, shriek inducing sequence, shows that he does love – Karloff adding his own texture on top of the visuals created by makeup artist Jack Pearce – transforming what easily could have been a one dimensional character into something much more. Likewise, Lugosi’s role was built from nothing (not appearing in the original script), Rowland Lee adding his own rewrites along the way, developing a dynamic henchman character that Lugosi could sink his prosthetic teeth into – the man would be forever grateful, for Universal was paying the actor a slim five hundred dollars a week (half of his usual salary – as he was in a slump) – and had ordered all of his scenes to be shot in a single week. . . instead, Lee kept him working the entire time, and gave him an onscreen persona that reinvigorated the Lugosi name.

Built on a Hollywood set nonpareil (by Universal art director Jack Otterson), the village Frankenstein is a German expressionist-style fairytale lingering on nightmare, the black and white cinematography (by George Robinson) perfection, the unsymmetrical lines mesmerizing, the scientific instruments electrifying, the foggy/boggy marshes Poe-esque. Playing overtop is Frank Skinner’s atmospheric score, featuring horns echoing from another world and strings that resemble the pounding of a tell-tale heart. . . a score that would be reused numerous times by Universal horror films in the 1940s.

Walking a tightrope between comedy and horror, Son of Frankenstein is an engaging film with wit and worries, cheekily quirky characters and chilling sequences, eccentric banter and eerie lighting. . . a unique mixture that lends itself to both re-watch-ability and being easily caricatured. Also, one almost throwaway line reminded me of the charm and mythical horror of these Universal features (most notably the Wolfman films) – for when Elsa inquires as to why the couples’ two beds are positioned so unusually, a foreign maid exclaims, “when the house is filled with dread, place the beds head to head” – how very ominous. So, discover the health benefits of these boggy, bubbling, sulphur baths and celebrate this major anniversary the right way – with two bolts in the neck and a stiff, big booted walk.