An Impossible Mission

How do you wrap up a franchise like Mission: Impossible? That is, if this even is the final installment... as they’ve made it sound (while at the same time, stars not named ‘Tom Cruise’ pipe up and suggest that might not be so). It has been twenty-nine years, with different writers and visionary directors – from twisty Brian De Palma and the action hair stylings of John Woo, to the lens flares of J.J. Abrams and animation expert Brad Bird, it was only about ten years ago that the franchise decided to opt for The Usual Suspects scribe Christopher McQuarrie for the final four. To return to that opening question once more, you could end with a Sopranos’ style cliffhanger, simply make another entertaining movie like the many before – like Everybody Loves Raymond did it with its final episode, or try to tie everything up in a neat little bow by bringing everything together as the Daniel Craig era did with James Bond. Well, it is definitely more along the lines of the latter example, with some distinct differences.

-

Chan Fan 2

Police Story 2January 5, 2020A sequel that picks up almost immediately where its predecessor left off, Police Story 2 finds our likeable officer, Chan Ka Kui (Jackie Chan) in a rather precarious position. . . reprimanded for his blatant destruction of the mall (in order to catch the villains at the end of the previous feature), not only is he demoted, but he also learns that all of his hard work was for naught – for drug kingpin Mr. Chu (Yuen Chor), who was supposed to spend life behind bars, has been released by a trifecta of doctors who have claimed that he only has three months left to live. Yet, this is only the beginning. . . throw in a spiralling out of control blackmailing case (in which a company’s holdings are being bombed), and more issues between Ka Kui and his spunky girlfriend May (Maggie Cheung), and we can easily say that he has his plate full.

-

What Could Have Been: Double Face

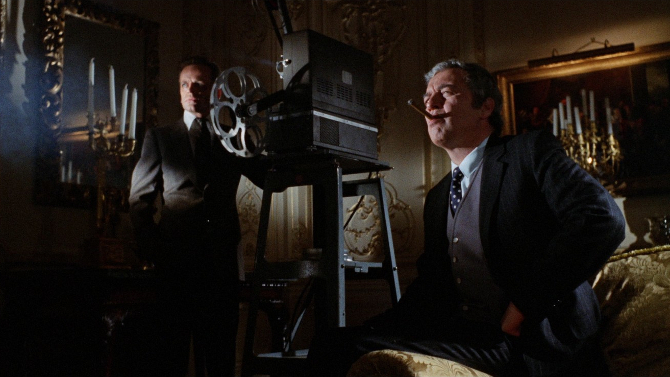

January 3, 2020The Swinging Sixties were a most unique time, especially in London. Often seen as a more traditional, conservative city, the growth of this young, wild child generation clashed with their aging parents and grandparents, a kaleidoscopic counter culture seeping into the stiff upper lip backbone of the nation’s capital. Capturing 1969 London in all of its variations, Double Face, co-written and directed by Riccardo Freda, follows one man’s unlikely journey through this often unnerving world. Klaus Kinski plays John Alexander (in a surprisingly reserved way), a wealthy, middle aged businessman with a much more traditional outlook. Quickly wedding extremely cash-happy Helen (Margaret Lee), it is a marriage that soon wallows into a depressing wake of clashes and affairs. Helen soon finds a lover, Liz (Annabella Incontrera), leading to questions of whether their union will last.

-

Fake News Film Facts. . . Vol. 2

December 30, 2019With this year quickly wrapping up, I thought that it would be fun to comedically reflect back on some of the films from the past year or two. To remind you of this Filmizon feature, what you will read are completely fabricated facts revolving around the movie world. Some will poke fun at silly aspects found (or ignored) in films, while others will satirize the supposedly real happenings of the movie world behind the scenes. Just in case you haven’t seen the films being poked at below, a very short synopsis has been added next to its bolded/italicized title. As always, feel free to try your hand at some movie comedy in the comments section below.

-

Take Note

A Beautiful Day in the NeighborhoodDecember 20, 2019Every once in a while, a feel good movie is just what is needed. Like a hot cup of cocoa, it can warm the heart, enliven the spirit, and bring comfort to the troubled brain. Just what the doctor ordered this 2019, A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood, directed by Marielle Heller, reminds us just how important a man like Fred Rogers is – even eighteen years after his final episode aired (and sixteen years after his death). Based upon the article “Can You Say... ‘Hero’?” by Tom Junod (published in the November 1, 1998 Esquire magazine), it is a story that juxtaposes the harsh realities of an embittered, emotionally angry investigative journalist, Lloyd Vogel (Matthew Rhys – The Americans), with the kind-hearted soul of PBS childhood icon Mr. Rogers (Tom Hanks), it just happens that Lloyd’s editor, Ellen (Christine Lahti), feels like it is the perfect time for the man to pull back on the reigns and do a lighter bio-piece on the beloved man.

-

You Better Watch Out…

Better Watch OutDecember 17, 2019If you’ve always thought that the Christmas classic Home Alone was a bit sadistic, you ain’t seen nothing yet. Better Watch Out, co-written and directed by Chris Peckover (the story was conceived by Zach Kahn – who also co-wrote the script), plays like a combination of the above mentioned Chris Columbus directed, John Hughes scribed film, and a twist on the home-invasion horror sub-genre – something along the lines of When a Stranger Calls or The Strangers. A tough sell during the holidays, Better Watch Out really didn’t deliver at the box office, yet, in its three years since its 2016 release, it has slowly built a cult following. Twisty as much as it is twisted, Peckover relishes in this horror-fused Hughes-style world. Set in an upper-middle class home, it could sit on the same cold wintery Chicago street found in the 90s gem.

-

An Irishman in an Italian Landscape

The IrishmanDecember 8, 2019Oh, how times flies – first they were Goodfellas. . . now they’re old fellas. Martin Scorsese re-teams with Robert De Niro, Joe Pesci, and adds Al Pacino (shockingly, the two had never previously worked together) to the mix in the 2019 film The Irishman. All kidding aside, it is fascinating how time changes things. Twenty-nine years ago the triumvirate mentioned above worked together on Goodfellas, three forty-something’s on the top of their game. . . arguably still on their respective games, they are all now north of seventy-five.