An Impossible Mission

How do you wrap up a franchise like Mission: Impossible? That is, if this even is the final installment... as they’ve made it sound (while at the same time, stars not named ‘Tom Cruise’ pipe up and suggest that might not be so). It has been twenty-nine years, with different writers and visionary directors – from twisty Brian De Palma and the action hair stylings of John Woo, to the lens flares of J.J. Abrams and animation expert Brad Bird, it was only about ten years ago that the franchise decided to opt for The Usual Suspects scribe Christopher McQuarrie for the final four. To return to that opening question once more, you could end with a Sopranos’ style cliffhanger, simply make another entertaining movie like the many before – like Everybody Loves Raymond did it with its final episode, or try to tie everything up in a neat little bow by bringing everything together as the Daniel Craig era did with James Bond. Well, it is definitely more along the lines of the latter example, with some distinct differences.

-

Jungle Love

Jumanji: Welcome to the JungleJuly 21, 2019A surprisingly original, unique and sharp take on video games (playing on numerous 90s video game tropes), Jumanji: Welcome to the Jungle updates the original Jumanji board game premise for the twenty-first century. An interesting layer of meta finds Jake Kasdan directing – son of Lawrence Kasdan (co-writer of The Empire Strikes Back, Raiders of the Lost Ark. . .), Welcome to the Jungle comes off as a quasi-combination of the two. . . the foursome who centre the feature are a ragtag team like in Star Wars, while the jungle adventure will immediately remind many of an Indiana Jones archaeology adventure – never a bad idea to create a hybrid of two of the most popular franchises in American history.

-

Chan Fan

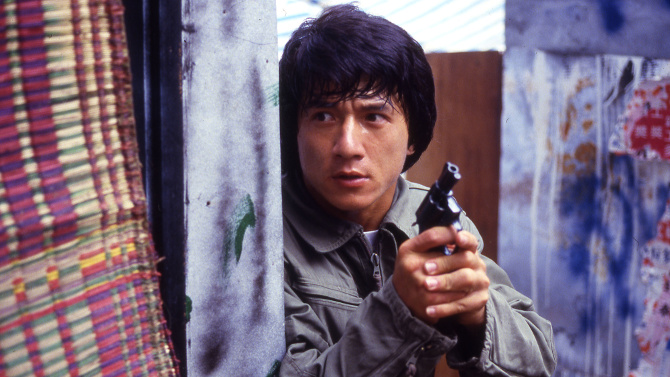

Police StoryJuly 16, 2019With some early success in China in the mid to late 1970s, Jackie Chan attempted to break into Hollywood – making appearances in The Big Brawl (1980), The Cannonball Run and its sequel (1981 and 1984), and starring in The Protector (1985). . . perhaps you would think that this was the beginning of his now illustrious career, but no. His supporting roles did not bring him fame in the west, while his first American starring role was a box office bomb. Instead of returning to China sunken and defeated, he began work on what would arguably become his greatest film, Police Story (1985), co-writing and co-directing with Edward Tang and Chi-Hwa Chen respectively. Taking on the starring role of Chan Ka Kui, Chan brings forth that appealing blend of comedic goof-ball and ninja mastermind – a more than likeable everyman who just happens to be a master of the martial arts (for most of his future roles, Chan would play slight variations on this iconic character – making him one of the most popular action stars of the past thirty years).

-

Spinning a Sequel

Spider-Man: Far from HomeJuly 12, 2019Walking a tightly strung web all the way from Queens, New York to historic Europe, Spider-Man: Far From Home has a few stumbles, but miraculously stays balanced on its epic journey. A sequel to 2017's Spider-Man: Homecoming, this 2019 adventure, which is also helmed by director Jon Watts, takes place almost immediately following the events of Avengers: Endgame (fear not, still no spoilers – though there are in this film), with Peter Parker’s Spider-Man (Tom Holland) struggling with his newfound fame (after all, he is still just a high school student). Dealing with questions like, ‘Is he an Avenger?’, or ‘What part does he play following the outcome of Endgame?’, he is like a spider in the headlights. . . looking for some much needed time off.

-

Star Pick with Elijah Wood

A Rabbit and a Gent Walk Into a Bar…HarveyJuly 9, 2019

A Rabbit and a Gent Walk Into a Bar…HarveyJuly 9, 2019How else can you start talking about Elijah Wood than referencing The Lord of the Rings – arguably one of, if not the best trilogy ever produced. Playing the lead character Frodo, he is the seminal everyman, or should I say everyhobbit, a down to Middle-Earth, caring individual with a larger than life spirit who takes on the task of transporting the most vile weapon of all-time, the one ring, into the heart of darkness to destroy evil for once and all. It is a performance of pathos, gravitas, and exquisite depth. Yet, one cannot forget Wood’s illustrious career. . . starting as a child actor, he graced the silver screen in pictures like Back to the Future Part II (a small part and his first film role), Avalon, The Good Son, only to further bolster his credits as a teenager with Flipper, The Ice Storm, and Deep Impact. Following the release of the above mentioned trilogy (2001-2003), Wood followed it up with solid turns in critically acclaimed features such as Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, Sin City, Paris, je t’aime, as well as voicing characters in the animated movies Happy Feet and 9. It must not be forgotten that he reprises his role as Frodo Baggins in the Rings prequel, The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey.

-

Stranger Than Pulp… Fiction

PulpJuly 2, 2019Just a year after making one of the greatest crime pictures ever to come out of the United Kingdom – 1971's Get Carter, the film’s three Michaels, producer Michael Klinger, writer/director Mike Hodges, and star Michael Caine reunited for a rather eccentric mishmash of genres and ideas – Pulp. Bringing together an all-star team of creative minds, on top of the above mentioned Michaels, the film is edited by iconic director of five James Bond flicks John Glen (his first, 1981's For Your Eyes Only, his last, 1989's Licence to Kill), cinematographer Ousama Rawi (perhaps best known for his excellent television work on shows like The Tudors and Borgia), while the music was composed by famed Beatles’ producer George Martin (often nicknamed the fifth Beatle).

-

Control Freak

They LiveJune 30, 2019Let’s face it, some movies don’t age too well, but if they’ve got the three main ingredients – solid writing, visuals, and acting, usually they can stand the test of time. One film that is still as timely today as it was back in 1988 is John Carpenter’s horror tinged sci-fi action film They Live. Welcome to Reagan era America, all trickle down economics, high unemployment rates and rising poverty. Set in ‘any city’ USA, Nada (Roddy Piper) is an out of work drifter looking for a semblance of the American dream. . . a job would be a start. Finally finding some employ on a construction site, fellow hard worker Frank (Keith David) takes him to a sort of shantytown, where the long travelling man can find a warm meal and a night’s rest.