An Impossible Mission

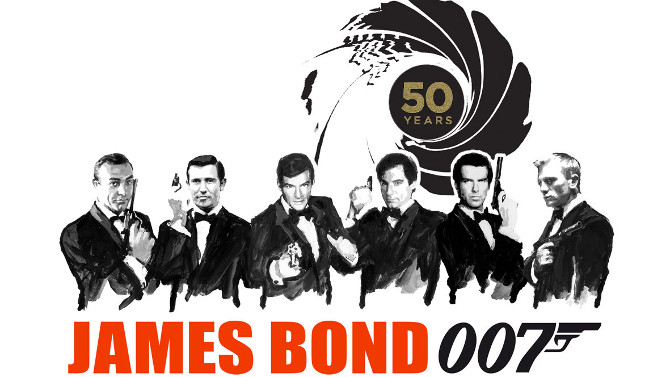

How do you wrap up a franchise like Mission: Impossible? That is, if this even is the final installment... as they’ve made it sound (while at the same time, stars not named ‘Tom Cruise’ pipe up and suggest that might not be so). It has been twenty-nine years, with different writers and visionary directors – from twisty Brian De Palma and the action hair stylings of John Woo, to the lens flares of J.J. Abrams and animation expert Brad Bird, it was only about ten years ago that the franchise decided to opt for The Usual Suspects scribe Christopher McQuarrie for the final four. To return to that opening question once more, you could end with a Sopranos’ style cliffhanger, simply make another entertaining movie like the many before – like Everybody Loves Raymond did it with its final episode, or try to tie everything up in a neat little bow by bringing everything together as the Daniel Craig era did with James Bond. Well, it is definitely more along the lines of the latter example, with some distinct differences.

-

Freeze Frame

The Forbidden Photos of a Lady Above SuspicionMarch 23, 2019I am not quite sure if I even need to write a review about this one. . . I’ll just tell you the title: The Forbidden Photos of a Lady Above Suspicion. One of those vividly descriptive yet cryptic giallo titles, Luciano Ercoli (Death Walks on High Heels) took his first stab at directing (pardon the pun) with this 1970 Spanish/Italian co-production written by Ernesto Gastaldi (The Case of the Scorpion’s Tail). The lady in mention is Minou (Dagmar Lassander), a bored housewife living a blasé life with her staid husband, Peter (Pier Paolo Capponi) – a man with a new invention that will hopefully save his struggling business (meaning that he is at work an awful lot). Getting no attention from Peter, she gets more than she bargained for when an unknown assailant (Simón Andreu) attacks her (with purpose) late one night while she is strolling near the ocean.

-

Star Pick with Guy Lafleur

A Legend Fleur Your Ice OnlyJames Bond FranchiseMarch 14, 2019

A Legend Fleur Your Ice OnlyJames Bond FranchiseMarch 14, 2019What is there to say about a legend like Guy Lafleur? One of the greatest National Hockey League players ever to feature in the game, he is synonymous with being one of the Montreal Canadiens’ holy triumvirate – along with Jean Béliveau and Maurice Richard. Transcendent of culture and language, in English he is known as “The Flower”, in French, “Le Démon Blond”, in either tongue, people would simply chant Guy!!! Immediately recognizable with his flowing blond locks, it always seemed like no one could touch the man as he flew down the ice (in a time when many players were still not wearing helmets – himself included).

-

Perspective Analysis

Four Times that NightMarch 10, 2019An Italian sex comedy with some class – I know, I know, that sounds like an oxymoron, the great Mario Bava (Black Sunday) co-adapts and directs Four Times That Night (1971), a film that structures itself in a similar way to Akira Kurosawa’s classic Japanese motion picture Rashomon – also, for a more modern example, think of the television series The Affair (starring Joshua Jackson, Dominic West and Ruth Wilson). Looking at one fateful night, four individuals get a chance to tell their side of the story. Dealing with perspective and viewpoint, the narrative revolves around Gianni Prada (Brett Halsey) and Tina Brandt (Daniela Giordano), a wealthy man always on the prowl – this time spotting a pious young woman in Tina.

-

Amor for Roma

RomaFebruary 24, 2019Alfonso Cuarón’s most personal film to date (even more so than Y Tu Mamá También), 2018's Roma seeps to the screen from the filmmaker’s own memories. . . a love letter to his beloved housekeeper who helped raise him in the neighbourhood of Roma in Mexico City all those years ago. His first Netflix feature, the streaming service gave Cuarón the freedom to create his vision his way. . . with a near limitless shoot time, the man not only directed, but also wrote, produced, co-edited, handled cinematography, and even shot the motion picture. Filmed in striking black and white, it is like seeing the most picturesque of monochrome postcards, but eerily intimate ones.

-

Oscar Predictions 2019

February 23, 2019Predicted winners, who should win, and my favourites from this year's Oscars (the 91st Academy Awards). Catch up on all the buzz before the big event.

-

What a Dick

ViceFebruary 21, 2019Some of you may get a little excited by the film I’m reviewing today – it features both bush and dick. . . get your minds out of the gutter everyone, this is obviously a look at the 2018 Academy Award Best Picture nominee Vice, written and directed by comedic turned dramatic filmmaker, Adam McKay. After reading the introduction describing the difficulties of making a film on one of the most secretive politicians in the history of the American political landscape – the one and only Dick Cheney (Christian Bale), the picture plays up its documentary style approach, jumping around more than a hyperactive kid playing hopscotch – from 9/11 to the distant past of 1963, only to bounce to 1969 – you get the idea.