An Impossible Mission

How do you wrap up a franchise like Mission: Impossible? That is, if this even is the final installment... as they’ve made it sound (while at the same time, stars not named ‘Tom Cruise’ pipe up and suggest that might not be so). It has been twenty-nine years, with different writers and visionary directors – from twisty Brian De Palma and the action hair stylings of John Woo, to the lens flares of J.J. Abrams and animation expert Brad Bird, it was only about ten years ago that the franchise decided to opt for The Usual Suspects scribe Christopher McQuarrie for the final four. To return to that opening question once more, you could end with a Sopranos’ style cliffhanger, simply make another entertaining movie like the many before – like Everybody Loves Raymond did it with its final episode, or try to tie everything up in a neat little bow by bringing everything together as the Daniel Craig era did with James Bond. Well, it is definitely more along the lines of the latter example, with some distinct differences.

-

Queen’s Reich

The FavouriteFebruary 12, 2019An out-there European director, Yorgos Lanthimos has made waves with controversial pictures like Dogtooth, The Lobster, and The Killing of a Sacred Deer – intriguing, confounding, frustrating, and mesmerizing audiences worldwide. Now, he has made his first foray into a more mainstream style of film making with the 2018 period piece The Favourite (the first picture he and longtime co-scribe Efthymis Filippou did not write – in this case, an excellent story by Deborah Davis and Tony McNamara) – though, one thing is for sure, you cannot take the eccentric out of the Greek filmmaker. Nominated for ten Academy Awards (including Best Picture, Best Achievement in Directing, and a slew of others), the first thing immediately noticeable is the feature’s striking visual style. Intricately measured and visually opulent (most of it is shot in Hatfield House, Hertfordshire, England), it is often symmetrically framed, a very formal seriousness to the playful story. Like the structured beauty of a perfectly danced waltz, everything is in its place, the camera moving with its characters always in their position, Lanthimos often utilizing a quick 180 degree pan pirouette to provide the viewer with a quick shot of the opposing perspective. Speed is also tinkered with, slow motion and a quicker frame rate adding to the film’s mesmerizing quality. Also worth noting, every once in a while there is a fascinating use of a sort of fish-eye lens-style shot – providing a distorted, arced look to this lavish, gilded world. Hand in hand with this is the exquisite cinematography, director of photography Robbie Ryan shooting almost the whole picture with available natural light (the sun, candles, fireplaces and torches providing an eerie, romantic, and realistic vibe, adding to Lanthimos’ trance-inducing visual style).

-

Busta Move

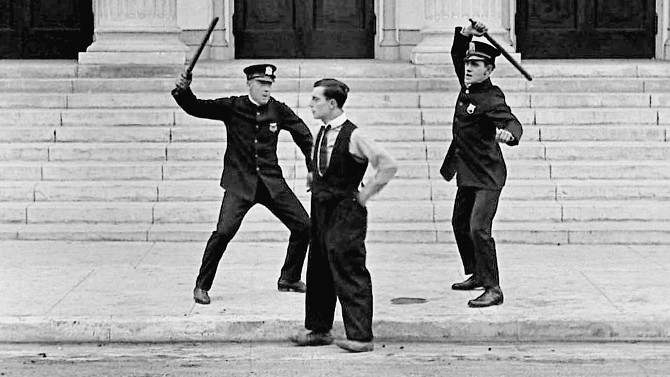

CopsFebruary 10, 2019A tale of visual trickery, rotten luck, and arguably, the bleakest of Buster Keaton’s shorts, Cops (1922) finds The Great Stone Face losing the girl (she is unwilling to even think of dating the man until he makes something of himself) – so, he heads out into the streets of Los Angeles (actually filmed on them) to do just that. Shot during the third trial of his good friend Rosco “Fatty” Arbuckle (charged with manslaughter), it is perhaps evident that the comic actor is not at his most cheerful. After making a few mistakes – Keaton’s use of the space onscreen and the items cleverly placed within it always awes and amazes, he accidentally purchases a cop’s furniture from a street scammer who has spotted that he has some dough (he also buys a horse and carriage that is not actually for sale). . . trotting away with the furniture in tow, he finds himself amidst a police officers’ parade and has the rotten luck of having an anarchist’s bomb land on the vehicle – completely unaware of what it is, he lights his cigarette with it, tossing it aside as it explodes (this idea very well could have come from fellow comedian Harold Lloyd, who, three years earlier, thought it would be funny to pose for photos as he lit a cigarette from the fuse of a bomb – it ended up being real. . . and the man lost his thumb, index finger, and a portion of his palm, it also left him partially blind for more than half a year).

-

Klandestine

BlacKkKlansmanFebruary 5, 2019It is hard to fathom that Spike Lee is now forty years into his film making career – and it has taken exactly that long for one of his motion pictures to earn a nomination for an Oscar for Best Picture, or Best Director for that matter (though he has been given an Honorary Award from the Academy). His first nomination came for his ‘Brooklyn cultural clash of love and hate’ screenplay for 1989's Do the Right Thing, and it is no surprise that 2018's BlacKkKlansman (which has earned six noms, including three for Lee – Picture, Director and Adapted Screenplay) holds a similar microscopic lens to the tensions smoldering just below the surface in the United States. At times excessive and over the top in its style, it is no surprise when you look at the time frame that the screenplay covers. Set in the early 1970s, it is a time of black and white thinking, radical movements such as the Black Panthers, the Ku Klux Klan, and even the police taking sides. . . the grey milieu forced to either side as cultures clash, as anger simmers to a boil, as times they are a changing.

-

We Will, We Will Rock You

Bohemian RhapsodyFebruary 2, 2019In my recollection, there has never been an Academy Award Best Picture nominee as contentious as this year’s Bohemian Rhapsody. With issues arising from the onset (supposed disputes during production leading to the film’s director, Bryan Singer, being replaced – Dexter Fletcher took over about two thirds of the way through, though Singer still holds the credit of director), it has since received mixed reviews from critics (with a measly 62% fresh rating on Rotten Tomatoes – extremely low for a Best Picture nominee), yet has been a huge box office success (already having earned over 800 million dollars, most fans have loved it, though there are a vocal group of naysayers). . . the most recent twist – the movie surprisingly took home Best Motion Picture - Drama at the Golden Globes, placing it in a rather intriguing position leading into the upcoming Oscars. A last note, a scene from the film with rather excessive editing has been spreading around the internet (look it up to get an idea of some peoples’ thoughts). The tale of the iconic rock band Queen, the narrative begins all the way back in 1970, wrapping at the band’s Live Aid performance in 1985. The biopic delves into all of the areas one would expect. . . the formation of the group, consisting of singer Freddie Mercury (Rami Malek), guitarist Brian May (Gwilym Lee), bassist John Deacon (Joseph Mazzello), and drummer Roger Taylor (Ben Hardy), their unique and unified way of making music, their dealings with their manager, John Reid (Aiden Gillen), lawyer, Jim Beach (Tom Hollander), record executive (Mike Myers – a nice casting touch, considering the classic Bohemian Rhapsody scene found in Wayne’s World), as well as groupies, their meteoric rise, subsequent trials and tribulations, and of course, the love that grows and fades, as well as the hate and disdain that builds up over the years (after all, what do you expect when rock star egos are involved?).

-

I Have a Dream

Green BookJanuary 27, 2019There is something special while watching an excellent drama and realizing, perhaps before, or maybe only after the credits role, that a director known almost exclusively for comedy has deftly made the genre switch. Think Jerry Zucker (from Airplane! and writing/producing The Naked Gun franchise to Ghost), Jay Roach (the Austin Powers and Meet the Parents franchises to Trumbo), or Adam McKay (Anchorman and Talladega Nights: The Ballad of Ricky Bobby to The Big Short and this year’s Vice). . . and the newest member to enter this club: Peter Farrelly – making the jump from Dumb and Dumber and There’s Something About Mary to 2018's Academy Award Best Picture nominee, Green Book. A tale near and dear to its writer, Nick Vallelonga (it is also co-written by Brian Hayes Currie and Peter Farrelly), Nick is the son of the film’s main character, Tony ‘Lip’ Vallelonga (Viggo Mortensen). Set in the early 1960s, Tony is an Italian American New Yorker, working as a ‘public relations’ expert for The Copacabana (i.e. a rough and tumble bouncer) – a pudgy bull-shitter who acts first and asks questions later.

-

Thanks For the Memories

The Long Kiss GoodnightJanuary 22, 2019Yearning for some 90s action? Are you missing the era of over the top, easy to watch explosive entertainment? Well, you cannot get more 90s than The Long Kiss Goodnight (1996), written by Shane Black (the scribe behind the Lethal Weapon franchise, and, more recently, The Nice Guys) and directed by Renny Harlin (of Die Hard 2 and Cliffhanger fame). Following a cryptic enigma in the form of Geena Davis (Harlin’s then wife), the actress plays Sam Caine (work the anagram out), an amnesiac of eight years. . . a teacher with a cute daughter, Caitlin (Yvonne Zima), and loving husband, Hal (Tom Amandes). Completely unaware of her past, the woman washed ashore two months pregnant. . . everything before this, a puzzling mystery.