An Impossible Mission

How do you wrap up a franchise like Mission: Impossible? That is, if this even is the final installment... as they’ve made it sound (while at the same time, stars not named ‘Tom Cruise’ pipe up and suggest that might not be so). It has been twenty-nine years, with different writers and visionary directors – from twisty Brian De Palma and the action hair stylings of John Woo, to the lens flares of J.J. Abrams and animation expert Brad Bird, it was only about ten years ago that the franchise decided to opt for The Usual Suspects scribe Christopher McQuarrie for the final four. To return to that opening question once more, you could end with a Sopranos’ style cliffhanger, simply make another entertaining movie like the many before – like Everybody Loves Raymond did it with its final episode, or try to tie everything up in a neat little bow by bringing everything together as the Daniel Craig era did with James Bond. Well, it is definitely more along the lines of the latter example, with some distinct differences.

-

Missed the Bloody Cut: 2018 (Part 1)

September 23, 2018A tradition that started last year, I decided that I would highlight some of the horror movies that did not meet my strict criteria (a rating of 7.0 or higher). . . as I realized that they are still entertaining films (horror fanatics may enjoy) that do not deserve to be left behind like the weakest link in a group of friends in a slasher flick – and that they are definitely worth a watch (just maybe not several re-watches). As you can imagine, I’ve been powering through a plethora of horror features as we speed towards Halloween, and, instead of posting one massive selection of Missed the Bloody Cut reviews at the end of October, I have decided to break it into two parts.

-

Watch Out for Big Red

Red-Headed WomanSeptember 21, 2018“So gentlemen prefer blondes, do they?” What a way to open a film. . . famed platinum blonde Jean Harlow, face wrapped in a hot towel at a beauty salon, utters this self-referential line (in many ways breaking the fourth wall and speaking directly to the audience – her hair now dyed red), only for things to delve into more intriguing terrain. . . the next snippet finds the dame trying on a dress – asking if you can see through the material, the shop worker answers in the affirmative, to which she perkily states, “I’ll wear it”. Vignettes with a purpose, each moment gives us a viewpoint into the world of one Lil Andrews (Harlow), a Red-Headed Woman with a plan.

-

Hope For the Best

The Cat and the CanarySeptember 16, 2018A horror premise as old as it is entertaining, Elliott Nugent’s 1939 film The Cat and the Canary finds an extended family coming together for the reading of their uncle’s will – ten years to the day of his death. A remake of the 1927 silent classic (the idea came from a 1922 stage play of the same name by John Willard), screenwriters Walter DeLeon and Lynn Starling fuse the narrative with a deft comedic touch, resembling the Abbott and Costello horror features that were soon to come – movies that were magically able to play the horror parts for horror and the comedy parts for comedy. Set in a gothic-style plantation home in the middle of the Bayou, the vines envelop the property, the alligator filled water and lush landscape swallowing the dilapidated mansion that likely once stood out, a grand example of man conquering nature. Somewhat resembling Poe’s House of Usher, the property is managed by a mysterious and menacing housekeeper, Miss Lu (Gale Sondergaard) – it is implied that she was the owner’s mistress, a woman who welcomes (and I use that word loosely), the estate’s lawyer, Mr. Crosby (George Zucco), as well as Cyrus Norman’s only remaining heirs: famed actor Wally Campbell (Bob Hope) – who keeps guessing what will happen before it does thanks to his profession, fetching Joyce Norman (Paulette Goddard), mother and daughter Aunt Susan (Elizabeth Patterson) and Cicily (Nydia Westman), as well as nephews Fred Blythe (John Beal) and Charles Wilder (Douglass Montgomery).

-

The Monster Gnash

C.H.U.D.September 14, 2018Full disclosure here: the film that I am going to review today is by no means a great movie. . . it is one of those rare pictures that transcends its low budget faults, somehow equating to late-night, cheesy goodness. A cult classic out of 1984, Douglas Cheek’s C.H.U.D. is a sci-fi film parading as a horror film, or is it a horror film parading as a comedy? Opening with a spectacular wide angle shot of a grimy, New York street in the middle of the night, a lady walks her dog, the camera slowly moving in until we only see a sewer grate, the canine and her feet (her shadow covering most of the shot). Dropping something, she reaches to retrieve it. . . and, in an instant, a giant monster-ish hand pops out from the metal cover, pulling both of the nightwalkers into the underground abyss.

-

Hello Kitty

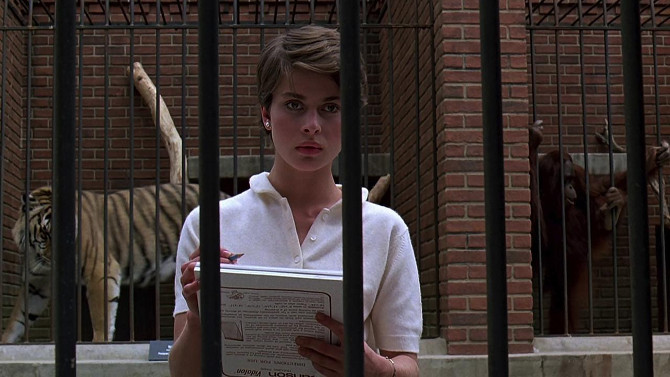

Cat PeopleSeptember 9, 2018Ah, the mysteries of the Black Panther. . . not Wakanda, vibranium, or the ever growing Marvel franchise, but rather, the enigma that is those giant cats that have been rumoured to be part human. First explored in the 1942 classic B horror film Cat People, reviewed here on Filmizon last October, director Paul Schrader remade it in 1982 under the same title, finding his own unique spin on the tale. Starting a little earlier than normal this year, this will be the beginning of a number of horror reviews leading up to Halloween (if you are not a horror fan, fear not, there will still be several non horror related pictures reviewed).

-

I Did It My Way

The Last FarmSeptember 7, 2018A meditative piece on aging, Rúnar Rúnarsson’s 2004 short film The Last Farm, out of Iceland, depicts a situation in which many of us will one day find ourselves in. . . old and decrepit, losing our freedom as we are forced out of our homes for a much more costly imitation of it. Hrafn (Jón Sigurbjörnsson) is an elderly man who has done it his way. Loving life on his little plot of farmland, it is stark yet beautiful, cold yet alive – a frigid ocean property surrounded by hilly mountains and dales, the meeting of land and sea picturesque in all of its challenges. . . unspoiled water and terrain for as far as the eye can see.