An Impossible Mission

How do you wrap up a franchise like Mission: Impossible? That is, if this even is the final installment... as they’ve made it sound (while at the same time, stars not named ‘Tom Cruise’ pipe up and suggest that might not be so). It has been twenty-nine years, with different writers and visionary directors – from twisty Brian De Palma and the action hair stylings of John Woo, to the lens flares of J.J. Abrams and animation expert Brad Bird, it was only about ten years ago that the franchise decided to opt for The Usual Suspects scribe Christopher McQuarrie for the final four. To return to that opening question once more, you could end with a Sopranos’ style cliffhanger, simply make another entertaining movie like the many before – like Everybody Loves Raymond did it with its final episode, or try to tie everything up in a neat little bow by bringing everything together as the Daniel Craig era did with James Bond. Well, it is definitely more along the lines of the latter example, with some distinct differences.

-

Back Space

It Came from Outer SpaceFebruary 4, 2018To provide a reference point, 1953's It Came From Outer Space comes off like a mix between an episode of The Twilight Zone and Star Trek, a science fiction horror tale with a message at its heart. A prime example of the way in which horror movies transformed in the Atomic Age (the fear of nuclear annihilation on the collective consciousness throughout North America and around the world), yet with a unique twist, director Jack Arnold brings Ray Bradbury’s story (adapted into a screenplay by Harry Essex) to vivid life. After the title explodes onto the screen, we meet amateur astronomer John Putnam (Richard Carlson – Hold That Ghost; Creature From the Black Lagoon) and his teacher girlfriend, Ellen Fields (Barbara Rush – she won Most Promising Newcomer - Female, for this film at The Golden Globes), who spot a giant meteor that hits the desert close to his home.

-

Extra! Extra! Read All About It!

The PostJanuary 31, 2018If you were formulating a modern day all-star cast and crew, you couldn’t do much better than The Post. Directed by the legend that is Steven Spielberg (three time Oscar winner and seventeen time nominee, as well as the recipient of the Irving G. Thalberg Memorial Award for “Creative producers, whose bodies of work reflect a consistently high quality of motion picture production”), Meryl Streep (three time Oscar winner and twenty-one time nominee), Tom Hanks (two time Oscar winner and five time nominee), composer John Williams (five time Oscar winner and fifty-one time nominee), cinematographer Janusz Kaminski (two time Oscar winner and six time nominee), and co-writer Josh Singer (Oscar winner for 2015's Spotlight), it is a veritable who’s who of the industry. Tackling the battle between the Washington Post and Richard Nixon’s government of the 1970s, Streep plays Kay Graham, the somewhat reluctant head of said newspaper. A woman in a man’s world, she has a difficult time transitioning from the non-working socialite wife to decision-making newspaper mogul. Tears always seem like they are soon to come as she clumsily drops things and nervously bumbles her way through this confusing world.

-

Strike… You’re Out!!!

StrikeJanuary 28, 2018An influential and innovative director that is sadly unknown to multiple generations of movie enthusiasts is Russian filmmaker Sergei Eisenstein, who would have turned one hundred and twenty a couple of weeks ago on January 10th. Best known for Battleship Potemkin (a laudable feature that will be reviewed here in due course), those in the know also point to his first full length motion picture, Strike, as being a vital piece of film history (it is often cited along with Orson Welles’ Citizen Kane as being one of the most audacious and impressive efforts by a first time filmmaker). Released in 1925 (the same year as Potempkin), though set in 1903, the aptly named picture, told in six parts, looks at a factory workers’ strike in pre-Revolutionary Russia. A fascinating study of early socialism versus capitalism from the Soviet perspective, the workers are close to their tipping point. . . looking for better hours, higher pay, less work for the child labourers and other such things. With the elite sensing their waning drive, they warn their spies on the inside to keep both eyes open for civil unrest – each of these men have an animalistic nickname, their personas connected to the beast they have been named for.

-

A Ray of Light in the Darkest Hour

Darkest HourJanuary 21, 2018Bringing to life the fierce bulldog, the prolific orator, the never wavering backbone of a nation during wartime that was Winston Churchill, Gary Oldman has placed himself as the early frontrunner as Lead Actor this Awards season (already having taken home the honour at The Golden Globes). Transforming into the stately politician by way of superlative make-up work and masterful acting, it is as if the man himself has been regenerated, mumbling growl and all. Before delving into the depths of Joe Wright’s Darkest Hour, I must indulge myself and pass along a few examples of Churchill’s legendary wit. Constantly at odds with fellow politician Lady Astor (the first female Member of Parliament), she targeted him by saying, “if you were my husband, I’d poison your tea”, to which he dryly replied, “Madam, if you were my wife, I’d drink it!”. Another retort finds Astor pointing out that he was drunk, to which he responded, “but I shall be sober in the morning and you, madam, will still be ugly”. This should give you an idea of what to expect from Anthony McCarten’s script – a Churchill-ism if I’ve ever heard one; “would you stop interrupting me while I am interrupting you”. Another one for good measure finds the man in the washroom while one of his aids tells him that he “needs to reply to the Lord Privy Seal”, to which he explains, “I am sealed in the privy, and I can only deal with one shit at a time”.

-

Babysitting is Dangerous

Adventures in BabysittingJanuary 16, 2018Going all the way back to Chris Columbus’s first directorial effort, 1987's Adventures in Babysitting is the way PG family films should be made, entertaining for both adults and kids, with just the right amount of edginess. Though incredulous, the entertaining narrative follows teenager Chris (Elisabeth Shue), who, after boyfriend Mike (Bradley Whitford) cancels on their anniversary dinner, grudgingly takes a job babysitting an adventurous eight year old, Sara (Maia Brewton), instead. Her older brother, 15 year old mild-mannered Brad (Keith Coogan), is supposed to be staying at his quirky buddy Daryl’s (Anthony Rapp), but after hearing that Chris is babysitting, sticks around.

-

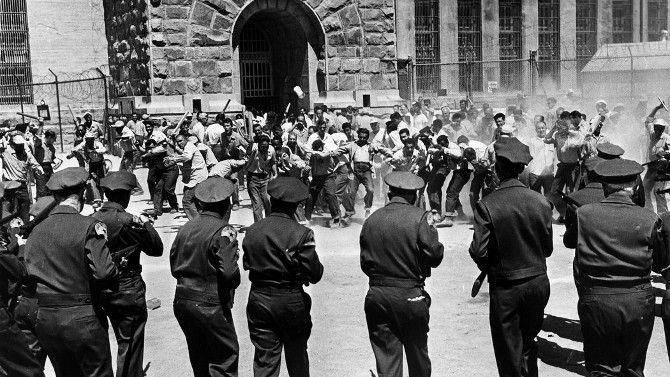

What a Riot

Riot in Cell Block 11January 14, 2018With a stellar cast, those behind 1954's Riot in Cell Block 11 did not take the approach of procuring the biggest names available, instead, they brought together a group of character actors that lived their parts – and all surrounded by real prisoners and guards, who played extras during production. Directed by Don Siegel (Invasion of the Body Snatchers; Dirty Harry), and produced by Walter Wanger (inspired to make the film after serving a four month prison sentence and being wholly unnerved – he was jailed for shooting his wife’s [Joan Bennett] agent, Jennings Lang, whom she was having an affair with – one bullet penetrated his hip, the other, his groin – clearly we know what he was aiming at), the team cast Neville Brand as a convicted murderer who heads up the riot (the former World War 2 combat soldier was the fourth most decorated American from the period), while his ‘Crazy’ second in command was developed by Leo Gordon (another convict who was shot in the gut during an armed robbery).