An Impossible Mission

How do you wrap up a franchise like Mission: Impossible? That is, if this even is the final installment... as they’ve made it sound (while at the same time, stars not named ‘Tom Cruise’ pipe up and suggest that might not be so). It has been twenty-nine years, with different writers and visionary directors – from twisty Brian De Palma and the action hair stylings of John Woo, to the lens flares of J.J. Abrams and animation expert Brad Bird, it was only about ten years ago that the franchise decided to opt for The Usual Suspects scribe Christopher McQuarrie for the final four. To return to that opening question once more, you could end with a Sopranos’ style cliffhanger, simply make another entertaining movie like the many before – like Everybody Loves Raymond did it with its final episode, or try to tie everything up in a neat little bow by bringing everything together as the Daniel Craig era did with James Bond. Well, it is definitely more along the lines of the latter example, with some distinct differences.

-

Star Pick with Kimberly Leemans

Double, Double Toil and TroubleHocus PocusMay 31, 2017

Double, Double Toil and TroubleHocus PocusMay 31, 2017One of those rare movies that has been slowly reappraised with time, Kenny Ortega’s 1993 Disney family flick Hocus Pocus was panned by critics upon its release. Much like other films, including It’s a Wonderful Life, television played a major role in its rejuvenation (as well as its release for home purchase), finding a more than willing audience each and every Halloween as part of ABC Family’s 13 Days of Halloween – grabbing well over two million viewers (record breaking numbers) and transforming it into a true cult classic. At the third annual CAPE (Cornwall and Area Pop Expo), I chatted with up and coming actress Kimberly Leemans. Getting her start on America’s Next Top Model back in 2007, she has transitioned into the realm of television and film. Perhaps best known for her turn as Crystal in the first Hilltop episode, 2016's "Knots Untie", in the hit television show The Walking Dead, she had the unenviable task of punching fan favourite Rick right-off-the-bat. . . she is then taken down by Michonne. Still wandering around in the zombie filled world, we will have to wait and see when she reappears.

-

House of Horrors

HouseboundMay 29, 2017Mixing horror and a long unsolved murder mystery with clever touches of comedy throughout, the 2014 New Zealand film Housebound, written and directed by Gerard Johnstone, is a twisty tale that constantly keeps you guessing. Playing with his audience, Johnstone provides little teases and possible red herrings as we go along: a mother, Miriam (Rima Te Wiata), phoning into a late night program telling of her run in with a ghost in her own home, a rough around the edges hoarder of a neighbour whose pastime just happens to be skinning animals, a murder that took place in the house the story is set in, an orthodontic retainer that may be a clue to who committed said murder, an agoraphobic neighbour who disappeared years ago, bizarre power outages, a missing cellphone, a creepy toy bear that keeps reappearing, as well as a supposedly haunted basement – all play their part in building the tense, suspenseful atmosphere.

-

Star Pick with John Stocker

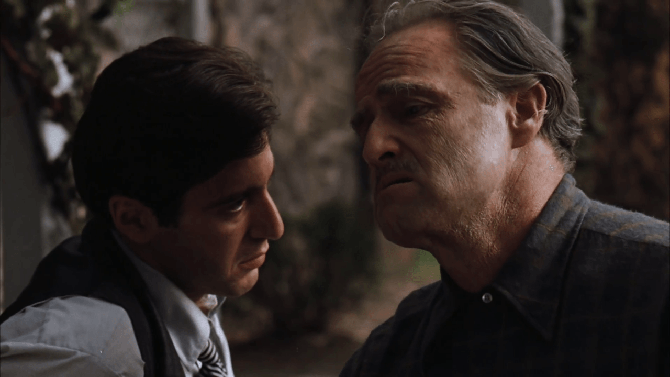

The VoiceThe GodfatherMay 26, 2017

The VoiceThe GodfatherMay 26, 2017Anyone who grew up in the 1980s to mid 90s will fondly recall the wide array of quality animated shows that graced the television screen. The Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, Rupert and Dragon Ball Z may come to mind, perhaps the only three shows that acclaimed voice actor, and today’s Star Pick John Stocker, did not do a voice on in this era of superlative children’s programming. Working since the 1960s, Stocker has been an integral part of the animated field for more than forty years. With one hundred and thirty seven acting credits alone, the sometimes voice director has an illustrious pedigree, to say the least. Beginning with perhaps his most acclaimed turn, henchman Mr. Beastly in The Care Bears, he gave the character a maniacal laugh for the ages, along with a rich, textured voice that brings to life the entertaining yet clumsy hijinks of the never successful villain who had a good heart deep down.

-

My Sweet ‘Star’-Lord

Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 2May 23, 2017Firing on all cylinders once again, writer/director James Gunn brings another entertaining, comedic, dramatic and all around fun feature with his 2017 Marvel sequel Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 2. Though it doesn’t capture the pure lightening in a bottle/giddy exuberance that the first one brought fans (though it is rare to find a sequel that can be as original, unique and exciting), this more than serviceable sequel has plenty to offer. Bringing the same entertaining mix of soulful characters, sharp dialogue, quirky humour, and surprising emotional heft, it also adds some new personas, small twists and important revelations that fill in many teasers put out there three years ago with the first volume. Many terms and words immediately come to mind after watching this second feature: dissension amongst the ranks, internalizing pain, sacrifice, family, dancing and. . . David Hasselhoff???

-

A Whole New ‘West’World

WestworldMay 21, 2017Many of you have probably heard of, and may be watching, HBO’s stellar hit show, Westworld. An intriguing premise to say the least, quite a few people do not realize that it is actually based on a 1973 movie of the same name, written and directed by famed novelist Michael Crichton – his first foray into the world of film making. Set in the not so distant future, this sci fi flick is infused with a classic western twist, as guests head to an amusement park to live out their fantasies in one of three worlds (Roman World, Medieval World and of course, Westworld). With a hint of being a precursor to a dystopic world, we are introduced to our two leads, first time attendee Peter Martin (Richard Benjamin) and his more experienced friend – at least, in relation to the very realistic park, John Blane (James Brolin), in a spacious, futuristic plane on their way to the locale.

-

Where the heART Is

MaudieMay 19, 2017An intimate character study, 2016's Maudie, written by Sherry White and directed by Aisling Walsh, fuses familial drama with Canadian East Coast humour. Beginning in the 1930's, the story is based on the real life of Canadian folk artist Maud Lewis – the titular character is brought to vivid life by the ultra-talented Sally Hawkins. Born with a bad case of juvenile arthritis, Lewis is a woman of strong will due to her affliction. With a bad limp, awkward disposition and secret from her past, she is seen by the community at large as being different. . . also, a stain upon their family according to her holier-than-thou Aunt Ida (Gabrielle Rose) and overly patriarchal brother, Charles Dowley (Zachary Bennett). One example of his ways – he sells off their parents’ home soon after their death without even telling his sister beforehand.