What Could Have Been: Shopworn

It’s usually hard to bet against Barbara Stanwyck. Starting her career in the late 1920s, within a few years she was already churning out star making roles as plucky working class girls who could rise to the top: think Ten Cents a Dance (1931) and Baby Face (1933) – both reviewed here on Filmizon, only to further elevate herself during the film noir era with starring roles like Double Indemnity (1944) and The Strange Love of Martha Ivers (1946) – also both on Filmizon, she even conquered television later in her career as matriarch Victoria Barkley in 112 episodes of Big Valley from the mid to late 1960s. In other words, it’s rather unusual to see her in a clunker... though with the film looked at here today, Shopworn (1932), directed by Nick Grinde, Stanwyck herself described it as, “one of those terrible pictures they sandwiched in when you started”.

-

Missed the Bloody Cut: 2021 (Part 1)

September 27, 2021A tradition every October here on Filmizon.com, I’ve decided that I would highlight some of the horror movies that did not meet my strict criteria (a rating of 7.0 or higher). . . as I realized that they are still entertaining films (horror fanatics may enjoy) that do not deserve to be like an unseen spirit, never to be noticed again – and that they are definitely worth a watch (just maybe not several re-watches). As the introduction to my month (and a bit) of horror reviews, I’ve already been powering through a plethora of horror features as we speed towards Halloween, and, instead of posting one massive selection of Missed the Bloody Cut reviews at the end of October, I have decided to break it into several parts.

-

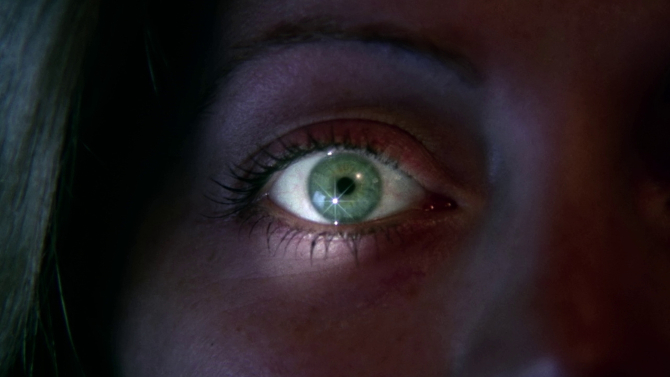

What Could Have Been: Death Has Blue Eyes

May 5, 2021Next time you see your friends, you might just want to take a gander into their peepers, for if we learn one thing in today’s feature, it’s that Death Has Blue Eyes (aka The Girl Is a Bomb). A 1976 Greek film written and directed by first time film maker Nico Mastorakis (though his more famous cult classic Island of Death was released first, it was in fact made second), this one is a mish-mash of C movie ideas rolled into a honey-trap of underwhelming baklava (sadly, the Greek pastry does not make an appearance in the flick). Feeding off of the James Bond and giallo craze of the time (as well as any other genre they could pop in), financed by the porn king of Greece, and with a budget so low that the writer/director would not earn one penny (or should I say drachma), in the end, it does intriguingly share some similarities with Brian De Palma’s Carrie – which was released the same year as this one. Keep in mind, perhaps, the fact that this is arguably the first supernatural film to be made in Greece – so maybe we can be kind in saying that it has a good concept that just isn’t executed particularly well.

-

What Could Have Been: Hitcher in the Dark

March 23, 2021In the late 1980s, Italian director Umberto Lenzi, best known for his giallo and horror fare – think Seven Blood-Stained Orchids and Knife of Ice, came to America to work with fellow Italian film maker Joe D’Amato (the man had been Lenzi’s cinematographer on 1970's A Quiet Place to Kill). Making four films together in two years, the one to be looked at here today is 1989's Hitcher in the Dark. . . a bizarre flip-the-script hybrid between the recently successful horror movie The Hitcher (1986) and the ever successful Alfred Hitchcock picture Psycho (1960). Following a mentally disturbed man in his early twenties, Mark Glazer (Joe Balogh) has a rather sick obsession (both sexual and violent) with his mother – the whole issue stemming from the fact she abandoned the family when he was only ten years old to schtup the local tennis pro (I’m sure the athlete is still claiming game, set, and match).

-

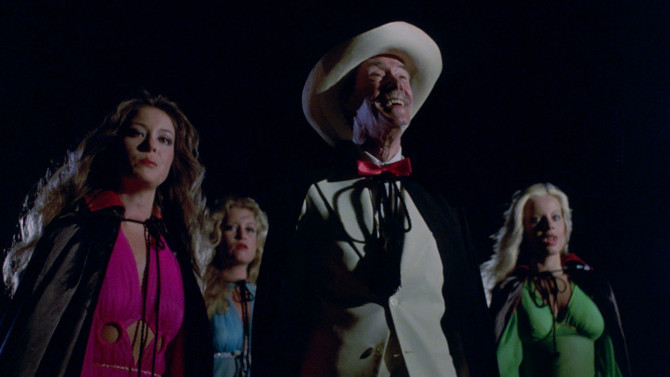

What Could Have Been: Vampire Hookers

March 5, 2021Every once in a while, you stumble upon such a film travesty, you just can’t wrap your head around how it can be so. At the 51st Academy Awards – held in 1979, “Last Dance”, a ditty from Thank God It’s Friday won Best Original Song, while the twangy rock tune, “Well, They’re Vampire Hookers. . . and blood is not all they suck”, the theme song from the American/Filipino co-production Vampire Hookers (1978), somehow didn’t even get nominated – go figure. A quirky exploitation horror comedy directed by Cirio H. Santiago, the premise is not actually half bad: furlough enjoying Navy men Tom Buckley (Bruce Fairbairn) and Terry Wayne (Trey Wilson) are fresh off the boat, looking for some fun in this undisclosed Asian locale. . . only to soon discover that, after a night of partying, their commander, CPO Taylor (Lex Winter), who was being chauffeured around the city by graveyard shift working taxi driver Julio (Leo Martinez), has gone missing.

-

What Could Have Been: The French Sex Murders

March 2, 2021If you’ve stumbled into the world of producer Dick Randall, then congratulations on being a part of a most bizarre level of film watching that most regular cinephiles will never reach. A fly by night producer (with a number of aliases – for example, Claudio Rainis in Italy) who knew how to talk the talk, he found money in the least expected places. . . in fact, it has long been rumoured that the reason he did not return to the United States was because he borrowed from the wrong people (some mobsters) when trying to get a couple Broadway plays up and running. A master (and I use that term lightly) of exploiting the most recent trend (think sexploitation, mondo, giallo, karate, even James Bond), this globetrotter jumped from one place to the next, spending some time in Italy, only to then make his way to the Philippines for another low budget project.

-

What Could Have Been: The Cut-Throats

February 21, 2021A film that can only be described as perfect weekend viewing for the great Quentin Tarantino, 1971's The Cut-Throats, written and directed by John Hayes, checks off all of the boxes. Featuring a bizarre western-infused introduction that has nothing to do with the rest of the flick (Django Unchained), a World War 2 set narrative (Inglourious Basterds), Nazisploitation (both Inglourious Basterds and Once Upon a Time. . . In Hollywood), a mostly confined setting (The Hateful Eight), a sword decapitation (the Kill Bill franchise), and quite a bit of foot fetish (the entire Quentin Tarantino filmography), hopefully you can really see what I’m talking about here.