River Rafting

Long before the wilderness of Alberta awed and amazed in Alejandro G. Iñárritu’s 2015 frontiersman epic The Revenant, it was widely featured in an impressive Technicolor CinemaScope picture, Otto Preminger’s 1954 western River of No Return. Shot in the beauty of Banff and Jasper National Parks (though some of the river scenes are shot at Salmon River in Idaho – where the actual story takes place), the scrumptious background is matched by the glorious foreground. . . which held two Hollywood greats – the chiseled features of Robert Mitchum and a woman whose looks need no descriptors, Marilyn Monroe (a rather intriguing historical note finds the actress causing a pile-up on the main street of Jasper while walking down the street in her tight-fitting jeans that she wears throughout most of the movie).

-

Star Pick with Damon Johnson

Grave ConsequencesTombstoneJune 6, 2018

Grave ConsequencesTombstoneJune 6, 2018It was an absolute pleasure to sit down with guitar guru Damon Johnson a few months back. The co-founder of Brother Cane, the band helped shoot Johnson onto the national scene – partially thanks to three number one hits on rock radio, namely: “Got No Shame”, “And Fools Shine On”, and “I Lie in the Bed I Make”. And, for horror fans, “And Fools Shine On” was used in Halloween: The Curse of Michael Myers (the sixth entry in the franchise). Disbanding in 1998, Johnson has been in demand ever since. He has worked (either touring or writing/recording) with Sammy Hagar (album: Marching to Mars), Faith Hill, John Waite, Whiskey Falls, Queensrÿche, Stevie Nicks, as well as many others (including his own solo projects). In 2004, he joined Alice Cooper as his lead guitarist. . . also co-writing and recording the superlative album Dirty Diamonds – some standout songs include, “Woman of Mass Distraction”, “Perfect”, “Dirty Diamonds”, and “Sunset Babies (All Got Rabies)”. On the road for five consecutive tours until 2011 (I saw them back in 2006), he was asked to join another iconic rock band, Thin Lizzy – Cooper gave him his blessing, and he made the jump.

-

Hostile Environment

HostilesJune 1, 2018There is a fascinating duality to the old west. Still mostly unsullied, the natural landscape was peaceful, serene, carrying with it an almost quiet solemnity (a new life filled with hope), yet, in the blink of an eye, violence could rear its ugly head, leaving behind a long lasting wake of pain, hurt, melancholy, and anger. An existential study of the clash of cultures, and the grey areas that sit in the large milieu between war and peace, Scott Cooper’s 2017 western Hostiles is a film that pays tribute to the past whilst speaking to the present unrest found in the world today. Centred around a man of conviction, stoic military veteran Capt. Joseph J. Blocker (Christian Bale), he has made his living off of slaughtering the native hordes that disrupt America’s Manifest Destiny. Called into the office of his superior, Col. Abraham Biggs (Stephen Lang), early one morning, he is less than pleased to learn that his final assignment (before retiring) will be to transport a cancer-riddled Cheyenne war chief, Yellow Hawk (Wes Studi), and his family, including son Black Hawk (Adam Beach), from New Mexico to his homelands of Montana – at the bequest of President Harrison. At first willing to disobey orders on his principles (Yellow Hawk was responsible for killing many of his colleagues and friends), the Colonel threatens to court-martial him and remove his pension – basically forcing him to take the job.

-

A Unique Take on the Traditional Western

McCabe & Mrs. MillerJuly 9, 2017We often think of the western as being set in the sunbaked, sand-filled deserts of the John Wayne and Clint Eastwood epics. Turning this idea on its head, Robert Altman takes us into the frontier lands of the wet and snowy northwest (filmed in and around Vancouver, Canada), an equally picturesque yet no less hostile terrain, in the 1971 film McCabe & Mrs. Miller. Riding into town with his bushy beard and no less hairy fur coat, John McCabe (Warren Beatty) is a businessman looking for his next big opportunity. He sees the tiny, half-built town of Presbyterian Church (just over one hundred people) not as a hindrance, but as the perfect location to set up a one stop saloon, gambling den and whorehouse. Hiring some local men, they get to work while he heads off to procure the working girls – purchasing some lower class ladies for the gruff, rough, and equally low class frontier men of the area.

-

Star Pick with Michael Dickson

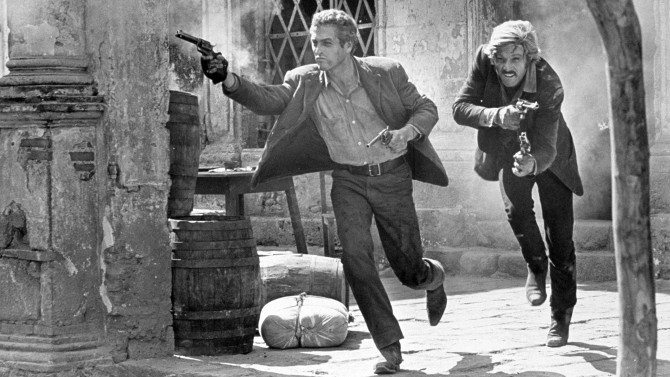

Butch and Sundance Ride OnButch Cassidy and the Sundance KidJanuary 24, 2017

Butch and Sundance Ride OnButch Cassidy and the Sundance KidJanuary 24, 2017One of the most prolific westerns (and sometimes argued to be the last great western) to come out of Hollywood, George Roy Hill adapts William Goldman’s script that brings to life the real, mythical-type figures of Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. The background of the script is quite something, with Goldman sending it out to all of the studios – only one was interested (and that was if he made a major change to it). Instead, a few minor adjustments were made, after which Goldman discovered that every studio in town now desperately wanted it. In the end, it was 20th Century Fox President Richard D. Zanuck (son of co-founder Darryl F. Zanuck) who purchased the screenplay for a whopping 400,000 dollars (the biggest sum ever spent on a script up to that point) – and 200,000 higher than he was allowed to spend. Putting his job on the line, it was a wise choice, as it became the highest grossing motion picture of 1969. Goldman ended up winning the Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay. Originally titled ‘The Sundance Kid and Butch Cassidy’, Zanuck didn’t find that the title sounded right when it was reversed to its final iteration – funnily enough, it now feels utterly awkward in its original form.

-

The Man with No Name

A Fistful of DollarsDecember 18, 2016Perhaps one of the most iconic introductions to a character finds Clint Eastwood’s Man with No Name riding into a dry, vile town, wearing the now legendary garb – dust covered poncho, brown gaucho-style hat, black jeans, spurs, and a Colt in his trusty holster (the stubby cigars will come a little later). Stopping for a drink of water, he takes in the violent, melancholic locale, where people gaze at him in a distrusting and ominous way through their wooden shutters, and children are shot at in the street by thuggish individuals. The first of what would become the "Dollars Trilogy" (or "The Man with No Name Trilogy"), A Fistful of Dollars, despite its now celebrated status, was poorly received by most North American and British critics when originally released. Once again showing how time is a fickle thing, the term Spaghetti Western (this type of motion picture), was first coined as a negative, disparaging term (ridiculing the European product for being of poorer quality to their American counterparts) – though today, it is generally thought of as an endearing and highly positive term. Directed by Sergio Leone, its unique visual style (beautifully framed close-ups that differ from the typical Hollywood use of the technique, as well as his then unorthodox use of viewpoint that places us in the moment over Eastwood’s gun), and attempt to move away from the traditional American tropes of the western, is now viewed as the beginning of the rejuvenation of the historic genre.

-

Star Pick with Chris Slade

Classic Western EnsnaresThe Magnificent SevenSeptember 20, 2016

Classic Western EnsnaresThe Magnificent SevenSeptember 20, 2016With the remake of the 1960 classic The Magnificent Seven coming out this week, I thought that it would be a good time to go back and revisit the original motion picture – though perhaps some will be surprised to find out that The Magnificent Seven is a remake of Akira Kurosawa’s iconic Japanese movie Seven Samurai. A while back, I was fortunate enough to chat with Chris Slade, the current drummer of AC/DC (who also performed with them during the years 1989 to 1994 – recording three albums with the high octane rock band: The Razors Edge, Live at Donington and AC/DC Live). Born in Wales, the percussionist has had a long and illustrious career, being the original drummer for fellow Welshman Tom Jones (and part of his first six records), as well as being a founding member of Manfred Mann’s Earth Band (recording eight albums along with Manfred Mann, Mick Rogers and Colin Pattenden from 1971 to 1978).