A Law Unto Themselves

The front door to an apartment swings open... an unseen figure walks through the living area and approaches a beautiful blonde woman wearing a robe as she walks around the bathroom... he then deliberately empties the barrel of his revolver into her – this is the jarring cold opening to the film noir Illegal (1955), and one thing is for sure, it knows how to grab your attention. Funnily enough, this was the third adaptation of the 1929 play “The Mouthpiece” by Frank J. Collins, following Mouthpiece (1932) and The Man Who Talked Too Much (1940) – and they say movies are remade too much today. Flash to Victor Scott (Edward G. Robinson), a district attorney who is wise to all the angles and is graced with a silver tongue. With an unyielding desire to win (he got it from growing up and fighting his way out of the slums), he argues every case like it is his last.

-

Twinkle Twinkle Little Stars

Night Has a Thousand EyesNovember 17, 2019Twisting the twinkling night sky into a harbinger of doom, 1948's Night Has a Thousand Eyes is a classic film noir that delves into the inexplicable realm of parapsychology. Based upon a novel of the same name written by iconic crime scribe Cornell Woolrich (and adapted by Barré Lyndon and Jonathan Latimer), John Farrow (Where Danger Lives; Around the World in 80 Days) directs this intriguing story. Opening in dramatic fashion, we witness a last second rescue of a young woman attempting suicide late one night at a bustling industrial railway depot (a stunning visual sequence).

-

French Kiss… Of Death

So Dark the NightNovember 15, 2019An overtly cheerful vacation romp to the French countryside. . . until it isn’t, 1946's So Dark the Night, directed by Joseph H. Lewis (Gun Crazy), transforms from unexpected romance to film noir murder mystery in the blink of an eye. Following famous Parisian detective Henri Cassin (Steven Geray), the man is finally getting his long awaited vacation. Though those within the station talk about his recent stress level, the portly, closing-in-on-retirement detective seems in very good spirits.

-

Saving Face

Dark PassageNovember 12, 2019The third of four films made by the husband and wife dream team of Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall, 1947's Dark Passage, written and directed by Delmer Daves (Destination Tokyo), is perhaps one of the most unique film noirs of the classical era. Not revealing star Humphrey Bogart’s face until sixty-two minutes into the movie, studio head Jack L. Warner (Warner Bros), upon learning this, was absolutely furious. . . but, the film was already so far into production that nothing could be done.

-

Short Cuts

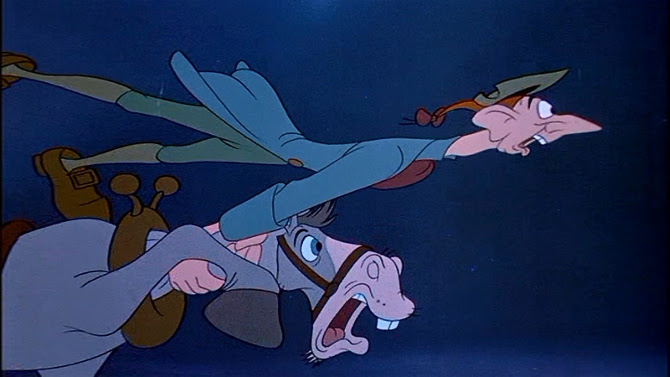

The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. ToadOctober 2, 2019Celebrating its 70th anniversary this 2019, Disney’s The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad (1949) is perhaps one of the most bizarre pairings of stories ever to hit movie theatres. . . Coupling Kenneth Grahame’s iconic children’s novel “The Wind In the Willows” with Washington Irving’s gothic horror story “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow”, you may be wondering what these two tales have in common. . . in short, absolutely nothing (it was actually due to reduced manpower during World War 2 that six movies – this being the last, were released in these combined and shortened formats). Woven together by a narrated battle of the greatest characters ever to grace British and American shores, English narrator Basil Rathbone (most famous for playing Sherlock Holmes) selects the former story, while Washingtonian Bing Crosby (singer/actor) highlights the latter. . . two more rich, melodious voices you will not find.

-

Like Father, Like Son

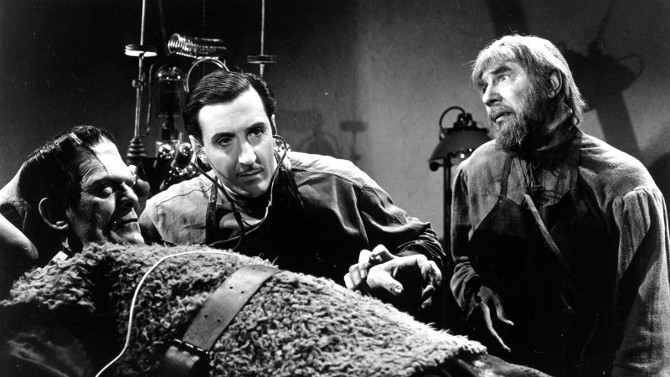

Son of FrankensteinSeptember 29, 2019Celebrating its 80th anniversary this 2019, the Son of Frankenstein (1939), directed by Rowland V. Lee, is the third film in the franchise – following Frankenstein (1931) and Bride of Frankenstein (1935), the last to feature Boris Karloff in the role of the monster, and the first to insert Bela Lugosi as Ygor. . . pairing two of the most iconic horror actors together was a smart move for Universal – the movie was a mammoth hit. All centred on the dramatic, pencil mustached Baron Wolf von Frankenstein (Basil Rathbone – arguably the greatest portrayer of Sherlock Holmes), he is the son of the original mad doctor. . . and is returning home with his slightly twitchy wife Elsa (Josephine Hutchinson) and young son Peter (Donnie Dunagan) – a cute, fear nothing lad whose accent is an eccentric delight, to claim his inheritance – much to the chagrin of the still terrified townsfolk.

-

Unlucky Number 13

Assault on Precinct 13September 23, 2019A lieutenant officer working the first day on the job, a group of prisoners being transported to a high security facility, a father and daughter looking for their nanny’s home, and a mysterious interracial inner city gang. . . what do they all have in common? They all almost fatefully find their way to an emptied police precinct on the verge of closure in John Carpenter’s 1976 low budget cult classic Assault on Precinct 13. Only John Carpenter’s second feature film, the writer/director weaves these four stories together, a doomed pacing drawing them all to one location for a single fateful night. The officer is Ethan Bishop (Austin Stoker), an African American working his first day on the job. . . given a seemingly uneventful task, he is the man in charge of the derelict Precinct 13 – a semi-closed location that will have its power and telephone lines shut off the next morning. The only remaining skeleton staff are: Sergeant Chaney (Henry Brandon) and a pair of secretaries, Leigh (Laurie Zimmer) and Julie (Nancy Kyes).