A Law Unto Themselves

The front door to an apartment swings open... an unseen figure walks through the living area and approaches a beautiful blonde woman wearing a robe as she walks around the bathroom... he then deliberately empties the barrel of his revolver into her – this is the jarring cold opening to the film noir Illegal (1955), and one thing is for sure, it knows how to grab your attention. Funnily enough, this was the third adaptation of the 1929 play “The Mouthpiece” by Frank J. Collins, following Mouthpiece (1932) and The Man Who Talked Too Much (1940) – and they say movies are remade too much today. Flash to Victor Scott (Edward G. Robinson), a district attorney who is wise to all the angles and is graced with a silver tongue. With an unyielding desire to win (he got it from growing up and fighting his way out of the slums), he argues every case like it is his last.

-

Universal House of Horrors

House of DraculaSeptember 27, 2020Celebrating its 75th anniversary this year (2020), 1945's House of Dracula, directed by Earl C. Kenton – Island of Lost Souls), is, in many ways, the last of the classic Universal monster movies. Although Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein and the three Creature from the Black Lagoon features would follow, this would be the final horror specific film that would centre upon their three most iconic monsters – Dracula, Frankenstein, and the Wolf Man (I apologize in advance for slighting the Invisible Man). Despite its slightly misleading title, all of the horror hijinks actually take place in and around the gothic castle of Dr. Franz Edlemann (Onslow Stevens), a surprisingly athletic older man (in reality, 43 years old) renowned for his dynamic and forward thinking form of medicine. Drawing the attention of Count Dracula (John Carradine), hiding behind the moniker of Baron Latos, and the perhaps more tortured than ever before Lawrence Talbot, a.k.a. the Wolf Man (Lon Chaney Jr. – the only actor to play the same monster every single time he appeared onscreen for Universal) – this time porting a mustache, both have sought him out – seemingly looking for a cure to their respective torturous affliction. Talk about quite the situation. . . Dracula moves into the basement, while Wolf Man takes residence in one of the upstairs bedrooms – not so sure if this a remedy for a good night’s sleep!

-

Grandma Knows Best

Grandma's BoySeptember 6, 2020Could there be anything more embarrassing than being a mama’s boy? Well, there might just be – being a Grandma’s Boy (directed by Fred C. Newmeyer). Silent comic superstar Harold Lloyd’s second feature length film following 1921's A Sailor-Made Man, this 1922 offering, like its predecessor, spawned out of a smaller two-reel idea, growing into a richer, more in-depth narrative. Coming out a year after Charlie Chaplin’s seminal first full length feature, The Kid, the fellow comedic actor was enthralled by his so-called rival’s film – describing it as “one of the best constructed screenplays I have ever seen on the screen. . . The boy has a fine understanding of light and shape and that picture has given me a real artistic thrill and stimulated me to go ahead”.

-

Dream of a Funeral and You Hear of a Marriage

3 Dumb ClucksAugust 17, 2020Some things never change. . . and by that I mean true love. . . and by that I mean the love found between a newly rich older man and a much younger woman. . . case in point, 1937's 3 Dumb Clucks, directed by Del Lord – a Three Stooges classic. Larry (Larry Fine), Curly (Curly Howard) and Moe (Moe Howard) have found themselves in jail. . . watched over by a very simple and overly helpful Prison Guard (Frank Austin). Receiving a letter from their beloved mother, she asks her boys to escape their confines and help bring their father home to her. . . as he has made millions through the oil fields he owns and has taken up with a young blonde gold digger, Daisy (Lucille Lund).

-

It Goes On and On My Friends…

The NeverEnding StoryJuly 22, 2020Oh, the 80's. . . a child’s mother dead, vicious bullies, a horse dying by way of depression in a boggy swamp, a killer wolf, a fantastical world coming to an end, heavy doses of existentialism – and that’s a children’s movie?! Of course, some of you might have guessed it by now, I’m talking about one of the most bizarre family films in the history of the silver screen, 1984's The NeverEnding Story. Co-written and directed by Wolfgang Petersen (in his first English language film – Air Force One, Troy and several others would follow), this German produced feature, based upon the 1979 novel of the same name written by Michael Ende, though successful in its original release, definitely falls within the cult classic moniker. With a 21st century lens, those who have not yet seen it will be shocked by just how dark and depressing it is for a so-called family film. . . but, like those original Grimm fairytales, just below its overtly bleak outlook, there are many more upbeat themes and life lessons to learn.

-

Bounty Hunters

For a Few Dollars MoreJuly 14, 2020Before we get started today, I just wanted to write something on Ennio Morricone, the iconic composer who passed away on July 6th, 2020. With a mind-blowing 519 composing credits to his name, he was a master of music. . . scoring everything from gialli (including Dario Argento’s famed “Animal Trilogy” – the first being The Bird with the Crystal Plumage) and spaghetti westerns (arguably his most famous work, the “Dollars Trilogy” with Sergio Leone) in his native Italy, to big budget Hollywood blockbusters such as Terrence Malick’s Days of Heaven, Brian De Palma’s The Untouchables, John Carpenter’s The Thing, Roland Joffé’s The Mission, Barry Levinson’s Bugsy, and Quentin Tarantino’s The Hateful Eight (which won him his only competitive Oscar). Today’s review of For a Few Dollars More (1965) is a prime example of his craftsmanship – a dynamic combination of diegetic and non-diegetic music (the former meaning a tune being heard by both the characters in the film and the audience, the latter being heard only by the audience), the score is built around the diegetic sounds of a musical pocket watch held by two different characters, yet this is only the beginning. . . listen for his fascinating combination of chanting, whistling, different sounds, and instrumental music that lingers somewhere between its nineteenth century western setting and some yet undiscovered post-modern style of music.

-

What Could Have Been: My Wife’s Relations

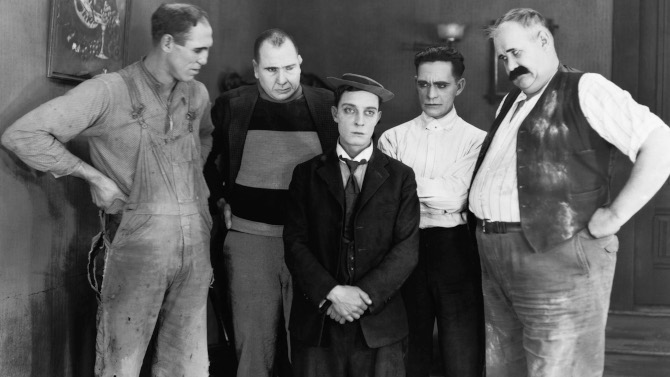

July 12, 2020Opening in a way only a Buster Keaton short film seems to be able to, an accidental confrontation between a mailman and the main character (leading to a letter, by chance, falling into the hands of the man, as well as a broken pane of glass as a result of the postal worker’s anger), followed by another clash between the always in the wrong place protagonist and a bullish woman – who assumes the diminutive man must have done the damage to the window. . . then throw in a Polish priest (who doesn’t speak English) making his own assumptions, and somehow, Keaton becomes Husband, and this woman, played by Kate Price, becomes Wife, in 1922's My Wife’s Relations, written and directed by both Buster Keaton and Edward F. Cline.