Voodoo, and Zombies, and Ghosts, Oh My

Beating the famed comedy duo of Abbott and Costello to the horror comedy circuit both one and two years prior to their 1941 classic Hold That Ghost, Bob Hope released The Cat and the Canary in 1939, following it up in quick succession (just eight months later) with The Ghost Breakers in 1940 – it was originally a play written by Paul Dickey and Charles W. Goddard (there are also two silent films from 1914 and 1922 based on it that are thought to be lost – the former being directed by Cecil B. DeMille). Directed by George Marshall, the mystery infused horror comedy follows a socialite, Mary Carter (Paulette Goddard), who has learned on a stormy New York night that she has inherited a supposedly haunted castle on a secluded Cuban isle ominously named Black.

-

Hope For the Best

The Cat and the CanarySeptember 16, 2018A horror premise as old as it is entertaining, Elliott Nugent’s 1939 film The Cat and the Canary finds an extended family coming together for the reading of their uncle’s will – ten years to the day of his death. A remake of the 1927 silent classic (the idea came from a 1922 stage play of the same name by John Willard), screenwriters Walter DeLeon and Lynn Starling fuse the narrative with a deft comedic touch, resembling the Abbott and Costello horror features that were soon to come – movies that were magically able to play the horror parts for horror and the comedy parts for comedy. Set in a gothic-style plantation home in the middle of the Bayou, the vines envelop the property, the alligator filled water and lush landscape swallowing the dilapidated mansion that likely once stood out, a grand example of man conquering nature. Somewhat resembling Poe’s House of Usher, the property is managed by a mysterious and menacing housekeeper, Miss Lu (Gale Sondergaard) – it is implied that she was the owner’s mistress, a woman who welcomes (and I use that word loosely), the estate’s lawyer, Mr. Crosby (George Zucco), as well as Cyrus Norman’s only remaining heirs: famed actor Wally Campbell (Bob Hope) – who keeps guessing what will happen before it does thanks to his profession, fetching Joyce Norman (Paulette Goddard), mother and daughter Aunt Susan (Elizabeth Patterson) and Cicily (Nydia Westman), as well as nephews Fred Blythe (John Beal) and Charles Wilder (Douglass Montgomery).

-

The Monster Gnash

C.H.U.D.September 14, 2018Full disclosure here: the film that I am going to review today is by no means a great movie. . . it is one of those rare pictures that transcends its low budget faults, somehow equating to late-night, cheesy goodness. A cult classic out of 1984, Douglas Cheek’s C.H.U.D. is a sci-fi film parading as a horror film, or is it a horror film parading as a comedy? Opening with a spectacular wide angle shot of a grimy, New York street in the middle of the night, a lady walks her dog, the camera slowly moving in until we only see a sewer grate, the canine and her feet (her shadow covering most of the shot). Dropping something, she reaches to retrieve it. . . and, in an instant, a giant monster-ish hand pops out from the metal cover, pulling both of the nightwalkers into the underground abyss.

-

Hello Kitty

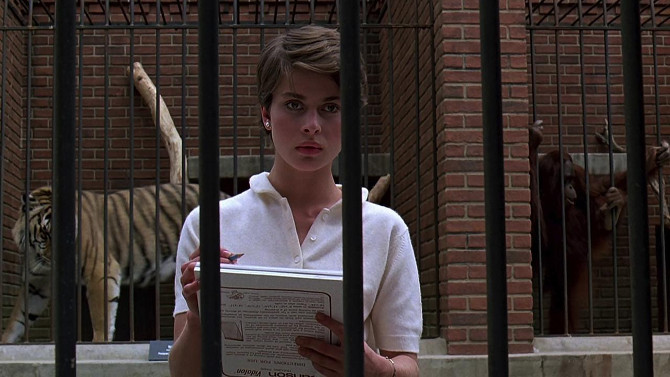

Cat PeopleSeptember 9, 2018Ah, the mysteries of the Black Panther. . . not Wakanda, vibranium, or the ever growing Marvel franchise, but rather, the enigma that is those giant cats that have been rumoured to be part human. First explored in the 1942 classic B horror film Cat People, reviewed here on Filmizon last October, director Paul Schrader remade it in 1982 under the same title, finding his own unique spin on the tale. Starting a little earlier than normal this year, this will be the beginning of a number of horror reviews leading up to Halloween (if you are not a horror fan, fear not, there will still be several non horror related pictures reviewed).

-

Fungal Infection

The Girl with All the GiftsAugust 31, 2018Children: those cute, innocent little scamps that bring a smile to our faces get a frightening makeover in Colm McCarthy’s The Girl with All the Gifts – a 2016 zombie horror flick out of Britain that finds some interesting new ground within the sub-genre. Finding a place somewhere between Day of the Dead and 28 Days Later, a small group of people have kept some normalcy at a military base (much of which is underground – similar to the former film mentioned above). . . mostly armed soldiers, the men fall under the control of Sgt. Eddie Parks (Paddy Considine), who only answers to Dr. Caroline Caldwell (Glenn Close) – a military scientist who has been tasked with researching the fungal outbreak that has caused a worldwide zombie-like plague (only the creatures are excessively fast, much like the latter feature referenced above).

-

Zombification

Day of the DeadJuly 4, 2018They first appeared late one night, which then led to the dawn of a new, more frightening day. . . now, they own said day – the third in George A. Romero’s anthology zombie franchise, 1985's Day of the Dead finds a small group of desolate individuals attempting to survive the ever growing and encroaching human eating hordes, a task that is easier said than done. Featuring a three pronged attack, Romero (who writes and directs) utilizes touches of German Expressionism, 60s psychological horror (think Roman Polanski’s Repulsion) and brutal gore to keep his audience on its toes. Our survivors are cloistered away in an underground military camp – a ragtag team pieced together in the final days of organized chaos to search for some sort of cure for the growing number of undead. They do, from time to time, head out in their helicopter, searching for survivors – the famed Edison theatre in Fort Myers, Florida, can be seen in the opening sequence.

-

Bloodlines

HereditaryJune 10, 2018The obituary – the last call, the final farewell, the closing shindig (likely the only remaining time you’ll be the centre of attention), basically a public invite looking for a person’s friends and family to come together for one last time to say goodbye, to tell stories, and to find some solace in closing the book on a man or woman’s story. . . but is it truly the end? Opening with an obituary, first time filmmaker Ari Aster’s Hereditary transports us into a reeling family dynamic, a group that have about as much promise in their lineage as the Usher’s (the Edgar Allan Poe characters, not the hip hop/pop artist). With mental illness coursing through their blood, Annie Graham (Toni Collette) did not exactly have a great relationship with her mother – often estranged, the elderly lady, who lived with dissociative identity disorder, ended her days dealing with dementia, further adding to the enigma that was her highly private life.